The most important reason for the positive investor sentiment during 2019 was the dovish turn in central bank policies at the beginning of the year. However, we think investors are overestimating the abilities of central banks to continue to facilitate economic growth.

Monetary policies are approaching their limits, which will make central banks more reluctant to implement additional accommodative measures. Going forward, the global economy can no longer rely on superhuman monetary powers of central bankers. In our view, sustainable economic growth can only be realised by increasing the productivity in the real economy. As productivity growth is stalling in advanced countries, we more than ever need a targeted investment agenda that stimulates ‘real’ economic growth, instead of the current financial agenda, which above all sustains elevated asset prices.

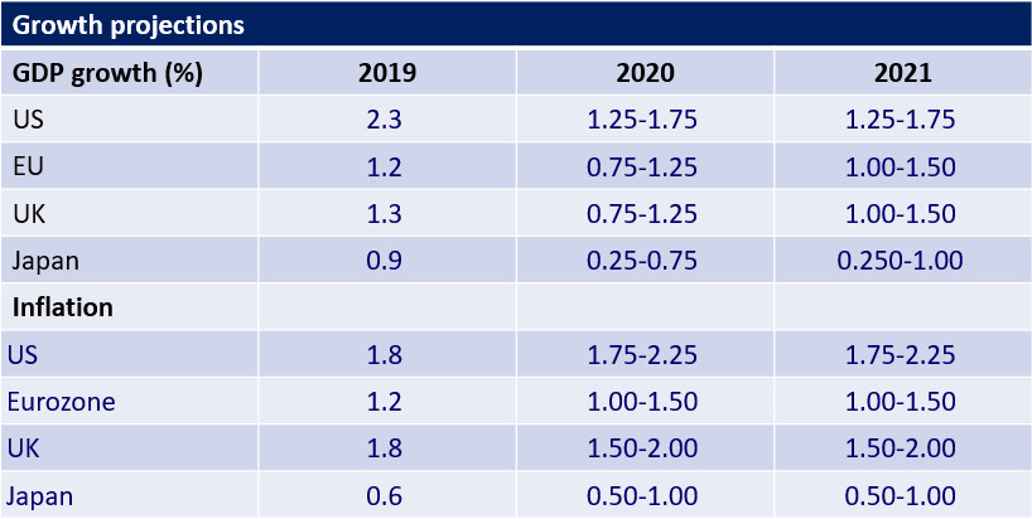

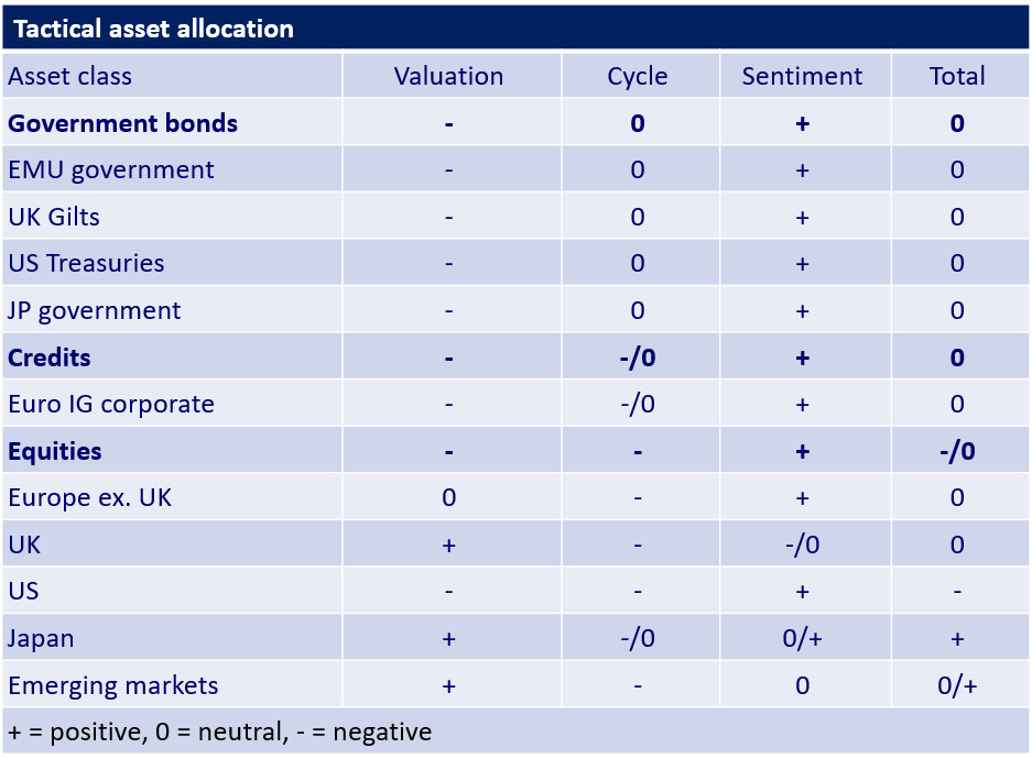

Predicting when the essential transformation to a new economic system will finally gain traction is difficult. The current situation – low growth, low inflation, low interest rates – can, as we know from Japan, continue for a long time. For now, the world has entered a period of economic stagnation. Given the geopolitical tensions and the diminishing effectiveness of central banks’ monetary policies, we take a cautious stance in our asset allocation. Therefore, we remain underweight in equities and neutral in bonds.

The illusion of fading geopolitical tensions

Towards the end of last year, the most important threats to geopolitical stability seemed to settle down. First, positive news on the finalisation of the ‘phase one’ trade deal between the United States (US) and China, which has been signed on January 15, made equity markets surge. Indeed, a complete and sustainable trade deal would severely reduce the worldwide uncertainty that has slowed down economic growth in 2019. However, the current trade agreement appears to be very limited. It does not remove most of the previously imposed tariffs and does not tackle several of the key issues that ignited the trade war in the first place.

Another of last year’s major uncertainties that appeared to be eliminated was the seemingly never-ending Brexit saga. Indeed, on the surface the finalisation of the withdrawal deal between the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK) and the subsequent outright majority election victory of Boris Johnson’s Conservative Party seem to pave the way for an orderly Brexit on 31 January this year. Both parties have less than one year, however, to agree upon an actual trade deal. As this seems unrealistic, we expect more Brexit-worries and discussions in 2020, putting further pressure on trade relations.

On top of that, recent escalations between the US and Iran have increased global uncertainty. Although tensions currently have slightly eased, the upcoming US presidential elections of November 2020 will make Trump’s decisions even more unpredictable. All in all, this leaves us in an undesirable environment as we are entering a period of global economic growth stagnation, where growth in the US, the UK, China and Japan is expected to slow, and growth in the eurozone is expected to stay in its current low gear.

The limits to monetary policy

In an effort to support economic growth and hence inflationary pressures, the world’s main central banks continued their loose monetary policies during the final quarter of 2019. In October, the US Federal Reserve (Fed) lowered interest rates for the third time that year. The European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) prolonged their ultra-loose monetary policies, and the People’s Bank of China, China’s central bank, cut interest rates for the first time in four years and loosened reserve requirements for banks. In our previous outlook, we already addressed the undesired effects of excessive easing: unrealistic high returns on the financial markets, only benefiting investors and multinationals and hence increasing global wealth inequality. However, as the easing policies are continued, the question arises if and for how long additional measures will be effective.

Recently, two former Fed chairs argued that the Fed is approaching its monetary policy limits, and might not be able to counter future economic downturns by itself. The most important reason for this presumed diminishing central bank effectiveness is the drop in the natural rate of interest. The natural rate of interest is an estimate of the interest rate that would apply without central bank intervention, i.e. when a neutral monetary stance is successfully maintained. Since the natural rate of interest has severely declined in all developed economies over the last twenty years and is approaching zero, there is little room left for additional interest rate cuts. Both the ECB and the BoJ are currently already deploying negative interest rates, and the Fed is moving closer to zero. Unconventional monetary policy tools such as asset purchases also appear to be less effective when the natural rate of interest moves below zero. A recent paper by the Bank of England shows that real interest rates have been declining since the late middle ages. The paper emphasizes that “irrespective of particular monetary and fiscal responses, real rates could soon enter permanently negative territory.” This development requires a whole new approach to central banking.

A new reality

It is time to acknowledge that the era of superhuman central bankers is coming to an end. Former ECB president Mario Draghi, ‘Super Mario’, has been replaced by ‘human’ Christine Lagarde, who is taking a more modest and studious approach. It is no coincidence that both the Fed and the ECB are in the process of conducting a strategic review, as they search for additional means to fulfil their mandates. Both Lagarde and Fed chair Jerome Powell have recently also suggested that governments should step in to complement monetary policies. Central bankers seem to realize that their current measures are losing in effectiveness and should be applied carefully. The recent move of the Swedish central bank, which ended five years of negative interest rates, could be a sign that central banks will put a hold on further easing in the near future. In the US, the Fed has hinted at keeping interest rates unchanged in 2020.

The main question now is: when will investors finally realise that central bankers have lost their superhuman monetary powers? When that happens, investor sentiment will rapidly turn.

A new reality includes acknowledging the fact that economic growth and hence market returns are becoming more and more financialised. Labour productivity growth has been slowing in recent years, a sign that investments are not used productively. The only way to counter this development is to implement an investment agenda that supports the transition towards a more sustainable world. This means focusing on investments in climate mitigation and adaption and the fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals in the next ten years. A public policy agenda such as the European Green Deal, which will hopefully gain momentum in the EU, would also help to steer public money into a productive direction. Perhaps that, in a different way, policy makers such as Frans Timmermans, Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal, take over the role of superhuman that central bankers are leaving behind.

In the end, all these transitions should lead to a new system based upon ecological economics, which recognizes “the fundamental importance of nature’s services and the biophysical underpinnings of human economies.” Monetary policies could also actively support this much needed transition if they would be ‘greened’, i.e. changed into policies that facilitate sustainable economic growth by addressing the most pressing issues for future generations. In this way, central banks can continue to play a vital role in our economy.

Caution is advised

The final quarter of 2019 saw rallying global equity markets, with new record-highs being reached in December. This rally contradicted the underlying economic indicators that showed a continuation of slow global economic growth and diminishing earnings revisions.

One of the driving forces behind the optimistic investor sentiment is the unlimited trust in central banks. Although monetary policies are already very loose, investors continue to expect that central banks step in whenever it seems necessary. Considering the relatively hawkish recent statements of the Fed, the chance that they will be disappointed is growing. On top of that, central bank measures are likely losing their effectiveness, and geopolitical uncertainties have all but disappeared. In combination with a global growth stagnation, this makes us tactically cautious on equity, since a more defensive allocation is the best way to guard against market corrections that have yet to materialise but in our view are coming closer.

Government bond yields slightly increased during the fourth quarter, showing a decrease in appetite for safe haven investments. We agree that recession risks for the immediate future have somewhat reduced but do foresee a prolonged period of growth stagnation. In this low-growth environment, materialization of one of the many geopolitical risks could result in a severe market impact. Our fixed income allocation therefore remains broadly neutral, and although the increase in liquidity makes defaults less likely, continued low growth makes us prefer credits with high-quality names.