The war in Ukraine has been raging for three months now, and the end is still not in sight. We see all kinds of policy reactions to the energy, food, and commodity crises that resulted from this conflict. All these reactions, whether with a short or long-term focus, shape the most important transitions of our times: the energy transition, the resource transition (circular economy), and the food and nature transition. Besides the argument that to safeguard the future of humanity we must avoid climate disaster and ecosystem crises, a more immediate argument has sprung up to help moving the needle in the right direction: geopolitical dependencies. In ‘Wartime transitions in Europe – Do we finally cross the bridge?’ we explored how the current situation could lead to a shift towards a more sustainable economy in Europe.

Finance as a catalyst for change: A second-best solution

Sustainability transitions – transitions in socio-economic systems that make the outcome and impact of these system more sustainable - do not happen by themselves. They require continuous action based on conscious choices. In our current system, if companies are allowed to pollute without costs and use nature’s resources beyond depletion – in economists’ words: as long as externalities are not priced in – markets will give unsustainable outcomes. Current financial regulation plays an important role in maintaining this situation, given that it primarily concentrates on financial stability and considers sustainability as a risk, rather than a necessity. It thus makes sense to have public policies correct these externalities also to reduce sustainability risks. Carbon pricing, rationing (limits), regulations and laws that help to create a level playing field or drive sustainable solutions would help starting and accelerating transitions.

Finance would quickly adapt to such an environment. In terms of risk-return, the most attractive options will be financed, while no considerations need to be made about the sector’s own moral obligations. There would be no need for extra labeling of what is sustainable finance and what not. This would be the ideal solution, in economists’ terms: the first-best solution.

Unfortunately, this is not how the world works. Politics does not and sometimes cannot do its job properly: vested interests, ranging from polluting companies to the rich (both individuals and countries) obstruct international coordination and preclude the construction of comprehensive plans that could accelerate transitions. Loss aversion of current generations hinder to serve the interests of future generations. As we do not have the time for muddling through, we must pursue second-best solutions to get sustainability transitions going.

One such second-best solution is to use the financial sector to catapult sustainability transitions, by using monetary policy, public finance, guarantees, and regulation, and by being fully transparency about the risks and impacts. This is currently the only feasible way to get things going.

Taking stock: Are we in transition?

A pressing question at this moment is if ‘things’ are moving in the right direction. From a transition point of view that direction should be: substituting fossil for renewable, reducing the use of metals, and making the food system more sustainable.

When we look at the financial flows, we can only sketch a very general picture for the food and nature, and the resources transitions. The financing gaps to fund the transition to a more circular, sustainable and regenerative economy are still large. With USD 4.1 trillion by 2050, there is a big financing gap for nature-regenerative activities. Most of the current amount of USD 133 billion in investments in nature-based solutions is provided by public sources. Part of this gap could be filled by private capital, especially from G20 countries. There are indications that the capital available for nature-based solutions is indeed increasing. Financing regenerative agriculture remains a challenge, however, although pledges are being made. An important part of the solution is therefore to limit – but preferably to stop – harmful investments.

For the resource transition the financing gap is completely unknown. No complete estimate can be made, mostly because circular solutions are presented as business opportunities. However, the ‘business opportunities’ delivered up till now, cover only a very small part of the total use of resources (less than 10%). In addition, most metals have a ‘lifespan’ of less than 10 years. The challenge is enormous, and it is quite evident that not all what is good from a circular perspective is financeable at this moment. Even if more and more private capital is flowing into circular solutions, it is still small compared to other transitions.

The picture for the energy transition is rosier, in the sense that there are more investment opportunities and things move quicker, also on the listed market. The estimated finance gap is nevertheless still large: USD 2-5 trillion annually by 2030 to avoid disaster – more than three times the current amount, also depending on sector, type of economy, and region.

Numerous financial institutions have meanwhile pledged to become net-zero. Some are aligned with the Glasgow Alliance for Net Zero, the Net Zero Banking Alliance, or other initiatives related to the quality of the targets set, such as Science-Based Targets initiative. In general, however, finance is not aligned with the Paris-goals. Progress is slow and – even more worrisome - persistently high levels of both public and private fossil-fuel-related financing continue to be a major concern, despite the net-zero commitments. Worldwide fossil fuel subsidies amounted to USD 5.9 trillion, or 6.8% of global GDP in 2020, and are expected to increase, not the least as a consequence of the war in Ukraine.

This is the longer-term picture. In the short term, what strikes first is that renewable energy stocks underperformed in general, while fossil fuel stocks outperformed since the beginning of the war in Ukraine. The oil and gas majors reported record profits in the first quarter because of the high oil and gas prices.

Although these are ominous signs, it is too early to speak of a derailed transition. First, higher interest rates, which are the result of monetary tightening by central banks trying to combat inflation, make growth stocks less attractive. Growth stocks are companies with high expected earnings in the future and at present show lower earnings or even losses. Discounting against higher rates makes the present value of the future cash flow lower and therefore also the valuation of the company. Second, markets always overreact. If energy prices normalise and hence profits for fossil fuel companies decrease, so will their valuations. Add to that possible policy reactions. In the UK, for example, the government announced it will tax oil companies’ ‘windfall’ profits.

Third, markets still suffer from the tragedy of the horizon, meaning that not all longer-term, negative effects have been priced in yet. Investors from rich countries face huge financial losses if climate action slashes the value of fossil fuel assets, despite many oil and gas fields being in other countries. An estimated USD 1.4 trillion in existing oil and gas projects would be lost if the world were to decisively cut carbon emissions and limit global heating to 2˚C. Research shows that most of the losses would be borne by individual people through their pensions, investment funds and share holdings.

The analysis also found that financial institutions have USD 681 billion of these potentially worthless assets on their balance sheets, far more than the estimated USD 250-500 billion of mispriced sub-prime housing assets that triggered the 2007-08 financial crisis. Rich country stakeholders therefore have a major stake in how the transition in oil and gas production is managed, as ongoing supporters of the fossil-fuel economy and potentially exposed owners of stranded assets.

Closing the gap

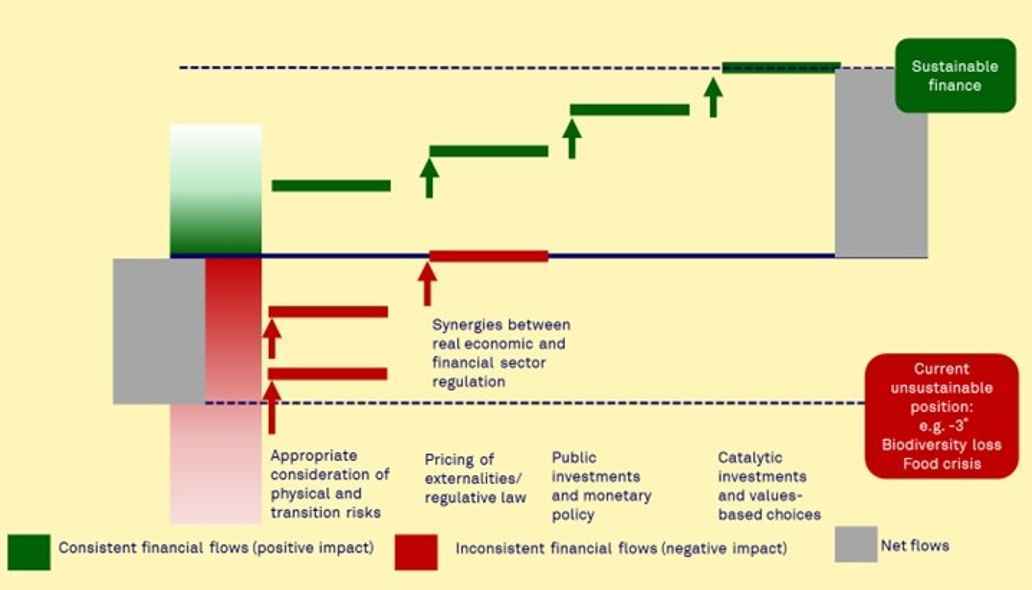

There are ways to help speeding up the financing of the highly needed transitions. Without going into the policy details, all transitions require:

- pricing in risks

- pricing of externalities and regulative law

- public investments and monetary policy

- catalytic investments and values-based decisions of financial institutions themselves

The figure shows how the gap in transition finance can be closed.

- Risks: Different kinds of risks – physical risks, transition risks, reputational risks – occurring in different transitions are currently not priced in, even though they are financially relevant. The period over which risks emerge (tragedy of the horizon) and the non-measurement of, for instance, nature or resource-related risks, make it hard to take notice of all risks. However, regulators are more and more looking into these different types of risk. The European Union, for instance, implemented regulation requiring asset managers to be transparent about the different kinds of sustainability risks in portfolio. Although this regulation currently mostly concentrates on climate risks, more is to come.

- Pricing of externalities and regulative law: Correcting financial flows, in the sense that all (long-term) financial risks are captured, is not enough. What is necessary is that the real economy is also regulated, and the regulatory environment of the financial sector directed towards transitions. What would help the energy transition is a global carbon price and measures for a just transition. And the circular economy would be stimulated if externalities in extraction (mining) and production were priced in. Agriculture and land use could become more sustainable if all adverse effects on ecosystems, including land erosion, deforestation, and emissions of greenhouse gases, were priced in. That makes all sustainable activities more financeable. Such regulation, however, is not likely to be implemented any time soon.

What will happen the coming years, at least in Europe, is the elaboration of the EU taxonomy. The EU taxonomy is a classification system, establishing a list of environmentally sustainable economic activities. It could play an important role in helping the EU scale up sustainable investment and transition finance. Currently, efforts focus on the first two objectives (climate change mitigation and adaptation) but the rest, including a transition towards a circular economy and protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems, is to follow in the coming years. Successful implementation depends on clear (science-based) definitions on what is sustainable and what not. This appears to be a very tough discussion – should natural gas and nuclear power be included? – and things do not look too promising, but it is better than nothing. - Public policies and monetary policy: Policymakers have powerful instruments to ramp up size and speed of the financing of the transitions. Public policies – giving the right incentives for private investors, blended finance, and public investments – can create a better investment environment to collect private capital. There seems to be more appetite for public spending on transitions in most developed countries, also before the Ukraine war. Currently, there are a lot of plans to invest publicly in (foremost) the energy transition in many countries, ranging from renewable infrastructure to energy saving. However, there is also a search for the best approach: should it all be public investments, or should public investments unlock private capital, either by setting the right conditions or by taking first risks. Blended finance is such an approach and can be used with a relatively small amount of public finance to leverage private capital towards transition finance.

Monetary policy makers also have a toolkit that they could use to speed up transitions. With their financial stability policy, they acknowledge that nature-related risks could have significant macroeconomic and financial implications. Because of this, an increasing number of central banks is performing climate stress tests. In addition to that, central banks could in the coming years also use their supervisory instruments to mitigate those risks, for instance by increasing capital requirements for banks that are not fit for transitions. - Catalytic investments and values-based decisions: A last element to speed up transitions is a more conscious use of money: values-based, forward-looking and in that way speeding up transitions (catalytic). In practice, this means that financial institutions more and more finance in such a way that they put both long-term and impact first and require a decent but not an excess or maximum risk-adjusted return. Triodos IM and other values-based banks have shown over the last decades that such an approach can make a difference.

A discussion that always follows, is what kind of capital is needed to close the gap: bank financing, private debt or equity, or listed instruments. They all have different risk profiles and are relevant in different parts of a transition. However, if steps 1-3 are taken, the risk profile of any private transition investment will decrease: it will become the new normal, with associated ‘normal’ risks. But that will take a long time. Currently, there clearly is a lack of investors who are willing to take risks: who are prepared to invest in transitions in for instance emerging markets, or in new, unproven but necessary technologies.

Do we have enough time?

A large finance gap needs to be closed. There are numerous instruments to do so. Changes in regulations in the real economy, changes in the financial sector itself, and the moral orientation and choices of the financial sector can alle accelerate the transitions. But the biggest question at this moment: do we have enough time? We have the tools, so why not use them faster, broader, and better? This is the question in the coming months: we need to speed up the transition. Not only for the longer-term sustainability goals, and apart from ending the war in Ukraine as soon as possible, but also to heat our houses next winter, to combat hunger, and to have metals and minerals at our disposal the coming years.

War in Ukraine

Read more about the impact of the war in Ukraine on financial markets and the macroeconomic implications.