The food system is suffering from overconsumption and overproduction of unhealthy and unsustainable foods, closely associated with increasing income inequality. About 820 million people remain undernourished, about 2 billion people are micronutrient deficient and over 2 billion adults suffer from obesity or overweight. At the same time, the food system is responsible for about 30% of GHG emissions and 70% of freshwater use, and the conversion from nature to agricultural lands is the main driver of biodiversity loss.

For the benefit of people and planet, we must revitalise the food system. We have compiled a get-well basket with healthy and sustainable products that illustrate our proposed interventions to build a sustainable food system: lentils, bananas, kale and walnuts.

Lentils - More sustainable and nutritious diets

Studies suggest that changing dietary patterns is perhaps the most essential step to transform the food system. Changes in our collective diets can deliver substantial health and sustainability benefits, as consumer behaviour influences the revenues of value-chain players. These players will move to sustainable alternatives if there is a proven market for it.

But what should our ‘new’ diet look like? The EAT-Lancet Commission recommends the Planetary Health diet, which is based on limited animal-based product intake and more fruits, vegetables, legumes and nuts. This includes eating more plant-based proteins, for example from lentils, for their low environmental footprint and association with lower risk of coronary heart disease. While this diet needs to be finetuned to include all required nutrients and circularity in food systems, it’s a good starting point.

There is a flip side to changing diets, however, which is why we need other solutions as well. Researchers at Wageningen University highlight that environmental benefits from dietary shifts could be nullified by rebound effects. For instance, consumers who may spend less money on food shift their disposable income to other high-impact goods. These rebound effects demonstrate the need for a comprehensive approach that couple dietary changes with other sustainability safeguards, for example through pricing mechanisms.

Bananas - Transparency and true pricing

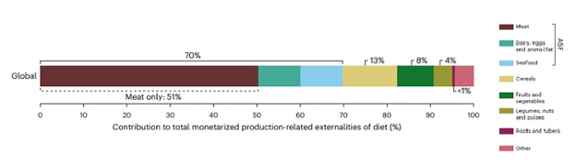

A recent study in Nature Food calculated the global environmental and human health costs of different diets and estimated that 70% of these costs can be attributed to the consumption of animal-sourced foods (ASF).

It is important that policymakers, retailers and producers invest in understandable labels or pricing systems that show these costs also on a product level. With such information, consumers, producers and other value chain actors can make different decisions. There is a need to create more transparency and for more agreement on methodologies and data needed to calculate ‘true prices’: the cost value of a product plus the environmental and social costs.

An icon of true pricing and transparency is the banana. A staple food for millions of people, the banana has a relatively straightforward supply chain. The banana was one of the first fruits to get Fairtrade and Rainforest Alliance certifications.

While labels help, sustainable bananas would benefit a lot from a level playing field in terms of pricing through taxes and subsidies. The information is there: the environmental and social costs of a box of bananas (18 kg) was estimated at USD 6.70 in 2017. Still, we should more broadly look what can enable consumers to make healthier and more sustainable decisions.

Kale - Strengthening consumer-producer connections

Local food systems can mitigate some of the negative impacts of the food system. Shorter and more direct food chains can offer more transparency and better negotiating positions for farmers when dealing with food retailers. Still, only about one third of the world’s population can fulfil nutritional needs by only eating local foods. Moreover, local food may have higher environmental impacts, as production could be more efficient in other places.

Transitioning to more local food systems is part of the solution, but the benefits should be balanced with the costs, depending on the product. Still, strengthening the connections between consumers and producers can potentially enable consumers to make healthier and environmentally friendly decisions. Such connections can also be fostered through online food platforms or by teaching consumers more about the origins of food, including its seasonality. In North-western Europe this would mean that we eat more kale during Winter.

Walnuts - Carbon-negative and nature-positive farming practices

Farmers alone cannot drive the necessary changes towards sustainable food systems, although their practices must also change to contribute to solutions. Agriculture is a major contributor to climate change and biodiversity loss, especially through the conversion of nature into agricultural lands and agrochemical pollution.

Nature-inclusive practices offer potential solutions. For example, food forests with fruit and nut trees like walnuts can sequester carbon, fix nitrogen, foster biodiversity and maintain high yields. Though inherently complex, this approach could be a potential win-win for ecosystems and rural livelihoods. Such landscapes can also integrate farm animals. Still, without changing diets and true prices, scaling markets for sustainable and healthy products may be largely infeasible.

No piecemeal approach

Food scientists are telling us: focussing on one solution or one part of the system will be too slow and can cause rebound effects. Instead, the food system requires a comprehensive ‘farm-to-fork’ transformation. Transitions in diets, pricing systems, food environments and agricultural practices are all elements of this transformation. The food system can be cured with appropriate remedies, but just an aspirin will certainly not be enough.