Our economist's insights: the Mid-Year Investment Outlook for Advanced Economies. It seems that the highly anticipated soft landing will really take shape for the aggregated advanced economies in the second half of 2024.

Global growth has become broader based

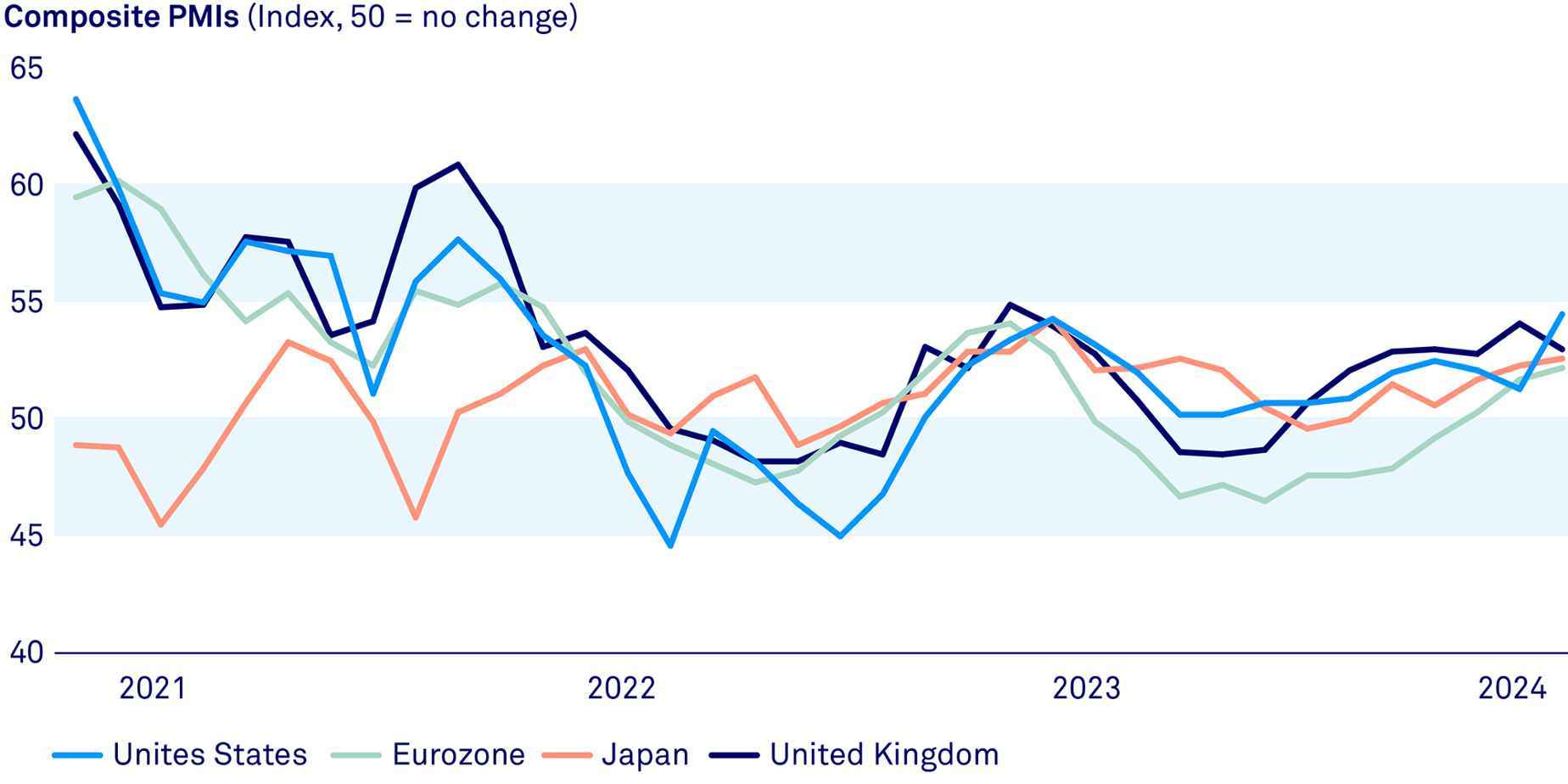

Since the end of 2022, the decent growth performance of the aggregated advanced economies masked a sharp divergence: it was almost entirely driven by the US. But in the first quarter of 2024, this trend came to a halt, with Europe returning to growth, albeit meagre. More recent indicators, such as the closely followed surveys of supply chain managers (PMIs), are also pointing to less divergence between the major advanced economies, mostly due to a pickup outside of the US.

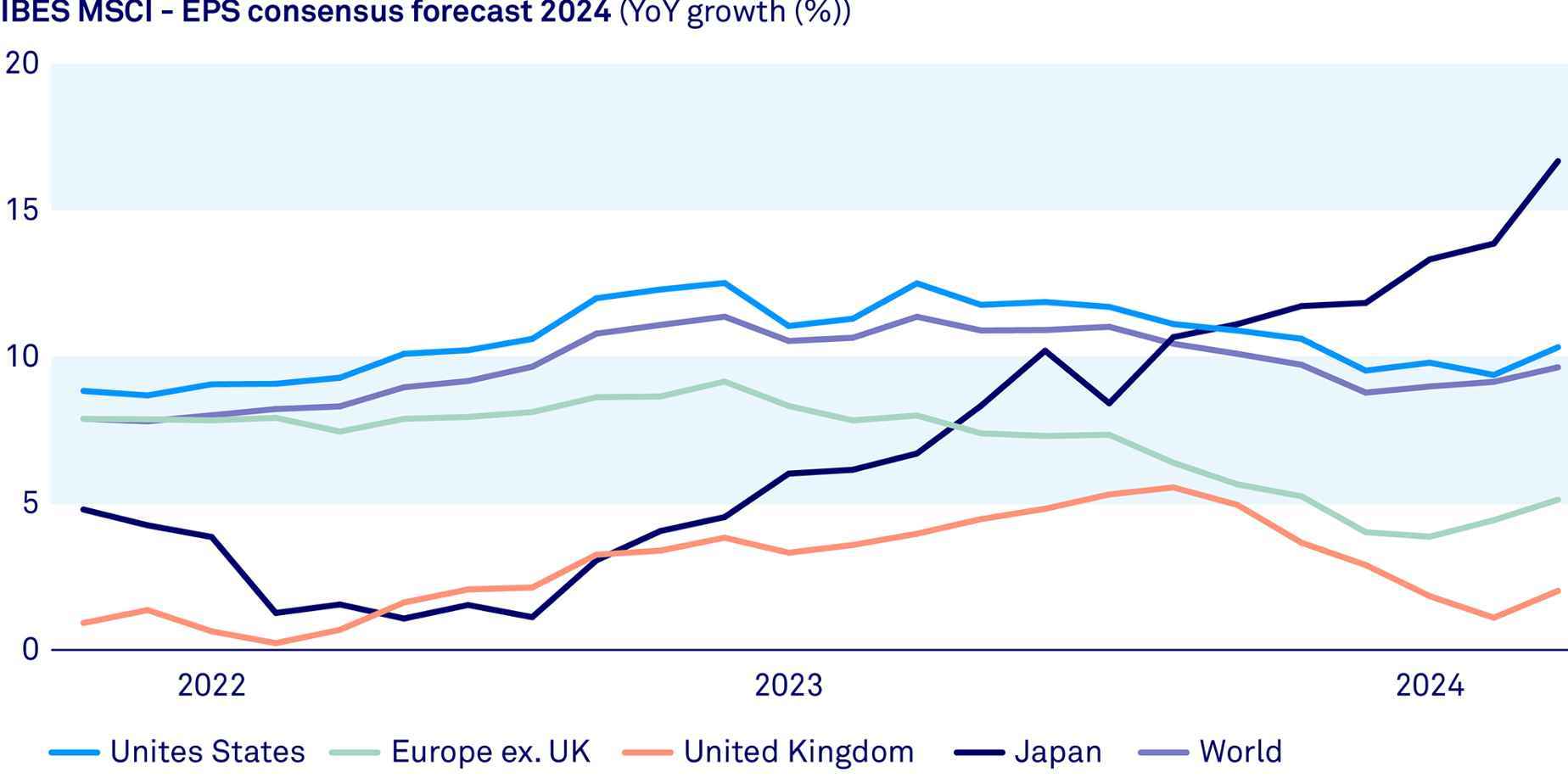

In line with this broadening of global growth, the most recent corporate earnings season was robust, with US earnings per share (EPS) growth still outpacing that of the eurozone, but with a narrowing earnings spread. On the back of these strong earnings, equity markets reached new record highs. Investors largely ignored the fact that investors priced out several interest rate cuts due to ongoing growth resilience and tight labour markets, which resulted in sticky core inflation.

Converging consumption prospects

We expect the recent momentum towards convergence between the major advanced economies to continue, driven by converging household consumption growth. The US consumer will likely finally take its foot off the pedal, because the excess savings that it had accumulated due to the huge fiscal stimulus have basically become depleted. Indeed, credit card delinquencies in the US are on the rise and retail sales have been stalling. The fiscal stance has also turned restrictive this year. We still expect moderate US consumption growth though, as still elevated wage growth combined with lower headline inflation means a gain in household purchasing power.

For the other major advanced economies, significant wage growth combined with easing headline inflation should result in a (further) consumption pickup. Households in these regions have been more cautious due to more modest fiscal support and higher energy prices. But despite the fiscal stances remaining restrictive, consumption can now recover from its very low levels as the energy shock has abated. Overall, this means a slight moderation in household consumption growth for the aggregated advanced economies.

Slowly unwinding services strength

As we expect only a slight moderation in overall household consumption growth, a key question for the inflation outlook across advanced economies is whether spending patterns will change. Services-related consumption has flourished since early 2023, while global goods consumption has lagged behind. The global manufacturing sector only returned to expansionary territory in February. Since the services sector is far more labour intensive, elevated wage growth across advanced economies has resulted in sticky core inflation. Therefore, for core inflation to ease further, demand for services should moderate.

Although it may happen slowly, we believe there is a likelihood of convergence between the manufacturing and services sector based on recent data. The reason could be that the COVID-related pent-up demand for services has finally run its course, or that products that were bought during the pandemic are due for replacement. The upcoming rate cuts could also be supportive of this consumption rotation, as lower borrowing rates could make large household durables more affordable. This anticipated moderation in services demand should be enough to take the heat out of labour markets and lead to a further moderation in wage growth.

Another important factor influencing core inflation going forward will be productivity growth. In the US, where risks of an extended period of inflation have been most severe due to an overheated economy, labour productivity has grown 6% since the end of 2019. Thereby, it has absorbed most of the rise in wages. As a result, unit labour cost growth in the US is currently far below the 2% inflation target, and unit labour costs are usually followed by core inflation. In the eurozone and UK, on the other hand, productivity growth has been roughly 1% over that same period. This would put these regions at more risk of an extended period of above-target core inflation. However, we expect that labour hoarding was one of the factors explaining this lower productivity growth, implying that labour markets in these regions are not as tight as thought. This should also limit wage growth going forward as services demand moderates.

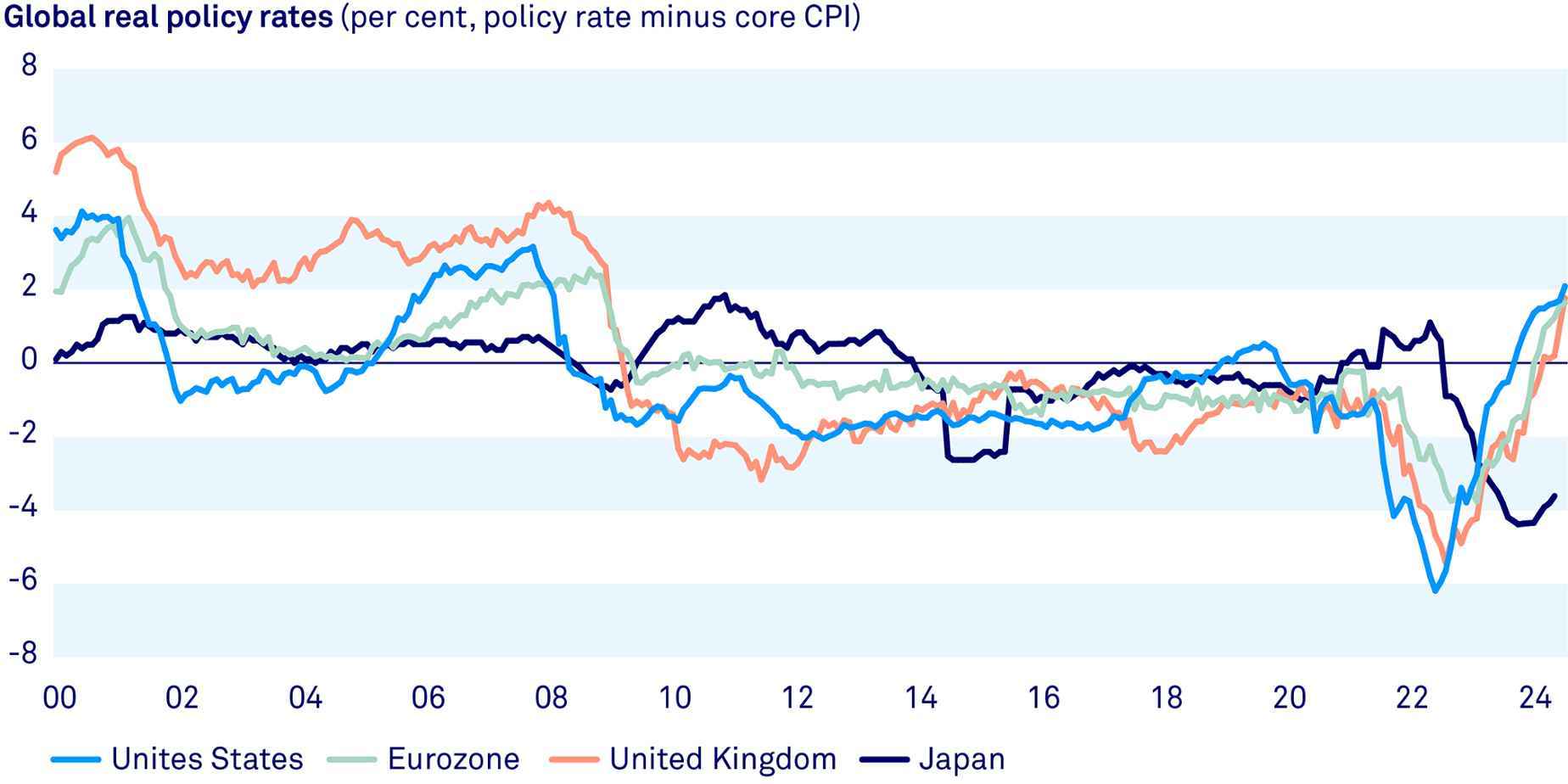

The effect of rate cuts may well be more limited than before

Given our expectations for convergence when it comes to household consumption growth and within-country sectoral strength (services vs manufacturing), we do not believe that there will be a significant divergence between the monetary policy of the major central banks (ignoring outlier Japan). The European Central Bank started its easing cycle in June with a first policy interest rate cut, and we expect two more rate cuts this year. We expect both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England to follow suit and cut twice in 2024. This is much less than expected at the start of 2024, but still slightly more than is currently priced in by markets. After that, we expect that these central banks will gradually move towards their neutral rates. Meanwhile, we expect the Bank of Japan to slowly increase its policy rate.

So far, the impact of the aggressive monetary tightening on economic activity has been relatively limited, with only residential investment taking a real plunge. Large businesses were able to lock in low interest rates before the tightening started, meaning the effects on business investment were far more limited. Now that real rates are set to fall again, it seems that a more severe impact of the monetary tightening will be largely avoided.

Eventually, the anticipated interest rate cuts should indeed lower real interest rates and thereby boost interest-rate sensitive expenditures. Especially residential investment should benefit from this. However, we expect the pace of rate cuts to be gradual, meaning real interest rates will stay high in the near-term, resulting in a still restrictive monetary stance. This means that it will likely take a while before rates are low enough to be a real support for investment growth. In the meantime, we still expect robust growth in US business investment, as corporates still benefit from a period of sustained corporate profit gains. Investment growth in the other major advanced economies will be more moderate in the near-term, following more moderate corporate performance.

Taking all the above into account, it seems that the highly anticipated soft landing will really take shape for the aggregated advanced economies in the second half of 2024. Nevertheless, the global expansion this year will be lower than the year before, meaning another year of global growth below this century’s historical average. For markets, a soft landing has been largely priced in by investors. Still, the start of the rate cut cycle has historically meant a strong performance in the year after the first rate cut. But this usually followed after a period of more muted market performance, as monetary tightening in the past had a more significant negative impact on economic activity and corporate earnings. We have not seen that same muted market performance this time around, with equity markets reaching new record-highs. Therefore, a strong rise in equity markets after the first series of rate cuts would be an illogical asymmetry.

Politics can affect inflation

Investors have so far ignored this year’s global geopolitical turmoil; both the ongoing war in Ukraine war and the Israel-Gaza war seem to have no effect on (near-term) corporate earnings and interest rates. If that is right, it is tempting to also label the recent elections in the EU and upcoming elections in the UK, France and the US as non-events for markets. Indeed, history has shown that this usually is the case. But this time around, we think it would be unwise to ignore the underlying political convergence across advanced economies that is taking shape, characterised by a shift towards more protectionism and right-wing conservatism, as this could push up inflation.

The increased chance of radical right coming into power has also heightened financial stability risks globally, as demonstrated by the recent turmoil in markets after the announcement of snap elections in France. Concerns arise for unrealistic budget plans that may result in excessive fiscal deficits, and in case of France, an outright increase in the existential risk for the EU.

Balanced view means neutral allocation stance

For the time being, we are sticking to our neutral equity allocation. This call is based upon several developments. We expect the global expansion to continue, albeit at a slightly more moderate pace (equal to a soft landing). We do not see immediate recession or severe slowdown risks to justify a move to underweight. Inflationary pressures are also expected to continue to gradually abate, which implies rate cuts by central banks going forward. This is usually beneficial for risk assets. However, the easing pace across the major central banks will probably be calm. In addition, rate cut expectations as priced in by investors seem realistic for now, but risks on inflation are tilted to the upside, with ongoing wars and a move towards protectionism. Also, earnings expectations are at seemingly high levels. Together, these factors do not provide sufficient basis for a move to overweight.

We are neutral in bonds in line with our balanced assessment of the global economy over the coming months. We believe that long-term yields will trend down slightly over the next half year from their current levels, which should provide some gains for bond investors. At the same time, we expect this drop to be relatively modest and notice bond yields reacting strongly to incoming data, which implies some volatility. Furthermore, it’s plausible that as policy rates come down and economic activity ‘normalises’ as along with monetary policy, the term premium is to build again. This could erode some of the potential gains on the long end, so we stick to a neutral stance and neutral duration allocation.