Almost half of all Windows computers worldwide still run on Windows 10, and as of 14 October 2025, 400 million devices that cannot upgrade to Windows 11 were scheduled to stop receiving free updates and support. Shortly before, Microsoft succumbed to pressure from civil society, agreeing to at least offer free support for one additional year. While positive, this action simply delays the decision users have to make on whether to buy a new device, start paying Microsoft for a temporary reprieve, switch to an alternative operating system, or continue using unsupported (and therefore insecure) software.

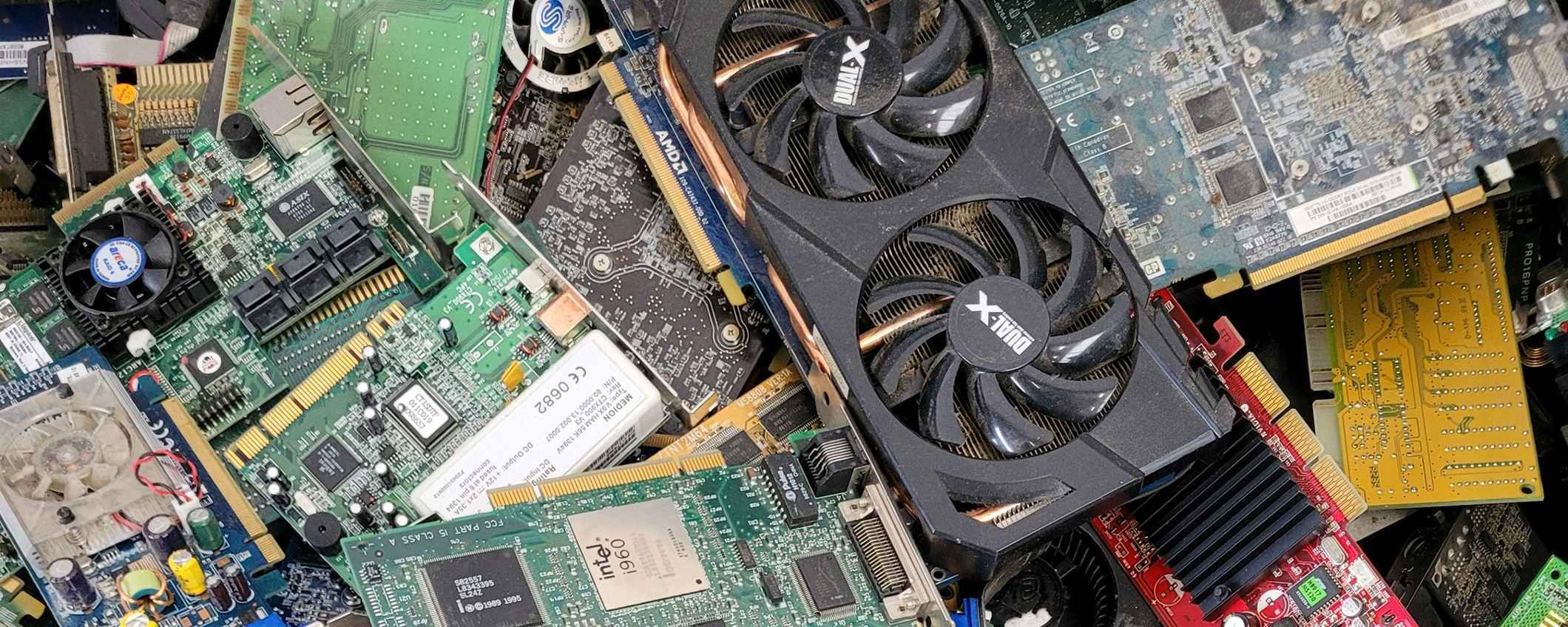

Many will likely opt for the simplest solution and purchase a new device with hardware that supports Microsoft 11. It is estimated this will generate 700 million kilograms of avoidable e-waste. Software-induced obsolescence is fast becoming one of the defining environmental challenges of our digital economy - how can we counter it?

Misleading narratives for investors

For investors, this episode reveals a blind spot. Tech companies are under no obligation to disclose how many devices they force into obsolescence, or the environmental costs of these decisions. Instead, their sustainability reporting will continue to spotlight narrow achievements such as renewable energy use in their data centres, while ignoring the resource sourcing and waste impacts inherent in their business models. A prime example is Apple, reporting proudly on green energy while remaining silent on the average iPhone lifespan, repair rates, or spare parts availability.

As a result, companies are rewarded for polished narratives, not for tackling the root causes of waste and overproduction. This causes misallocation of capital, where investors end up financing the best stories about change, instead of real change.

A further issue is that when systemic waste remains invisible, capital markets can misjudge and misprice companies’ environmental liabilities. This kind of mismatch undermines environmental goals and creates financial risks once regulators, insurers, or consumers finally start factoring these hidden costs into the price of doing business.

A modular approach to hardware design

While software-induced obsolescence is a key driver of e-waste, a root cause of the issue is the design of the hardware itself. As newer software demands more processing power, many older devices become unable to keep up because they were never built to evolve. That’s why the real solution is in rethinking hardware design to make devices more modular, repairable, and upgradable. Fairphone is a great example of this principle. Their business model demonstrates that it is possible to have software progress and reduce hardware waste at the same time (by allowing users to replace or enhance individual components rather than regularly discard their devices). Investing in companies that apply these modular design principles could help align technological innovation with circularity and reduce some of the negative environmental impacts inherent in existing business models.

Reporting that hides vs. reporting that helps

The pattern of disregarding sustainable design and negative impact across product lifecycles is not limited to tech, it occurs across industries. Fast fashion brands often emphasise the share of recycled or “sustainably sourced” fibres in their garments but do not disclose repairability, durability, or end-of-life material recovery. As a result, mountains of textile waste are hidden.

There are, however, positive outliers. Patagonia reports on repair statistics and tangible efforts to extend product use. Fairphone also publishes data on average device lifespan, spare parts availability and longevity improvements created by their modular design. Such reporting should be standardised across their respective industries.

Shortcomings of existing standards

Under the latest ESRS E5 draft, tech companies would still not be required to report on consumer waste, even if it is directly caused by their business model. We spoke to Cristina Ganapini, Coordinator of the Right to Repair Europe coalition about the three loopholes left by the draft.

Firstly, when it comes to product disclosure, the ESRS requires companies to report on the expected durability and scope of reparability of their key products. In the Microsoft example, these “key products” are primarily software, not physical devices. Secondly, for waste disclosures, the ESRS requires reporting on waste streams from a company’s own operations (in this case servers, office waste, packaging). The discarded laptops and PCs don’t fit here, because that waste arises in consumers’ hands, not in the company’s factories or data centres.

Lastly, waste disclosures are only mandatory if they are assessed as “material” by the company itself. This means they can decide themselves whether forced hardware obsolescence is important enough to disclose. Given the reputational and financial implications, it is easy to imagine they would conclude it is not.

Regulation needs to go further to explicitly require disclosure of post-consumer waste caused by a company’s business model, but investors also must ask the right questions to encourage companies to design for modularity, repair, reuse – and most importantly, longevity.