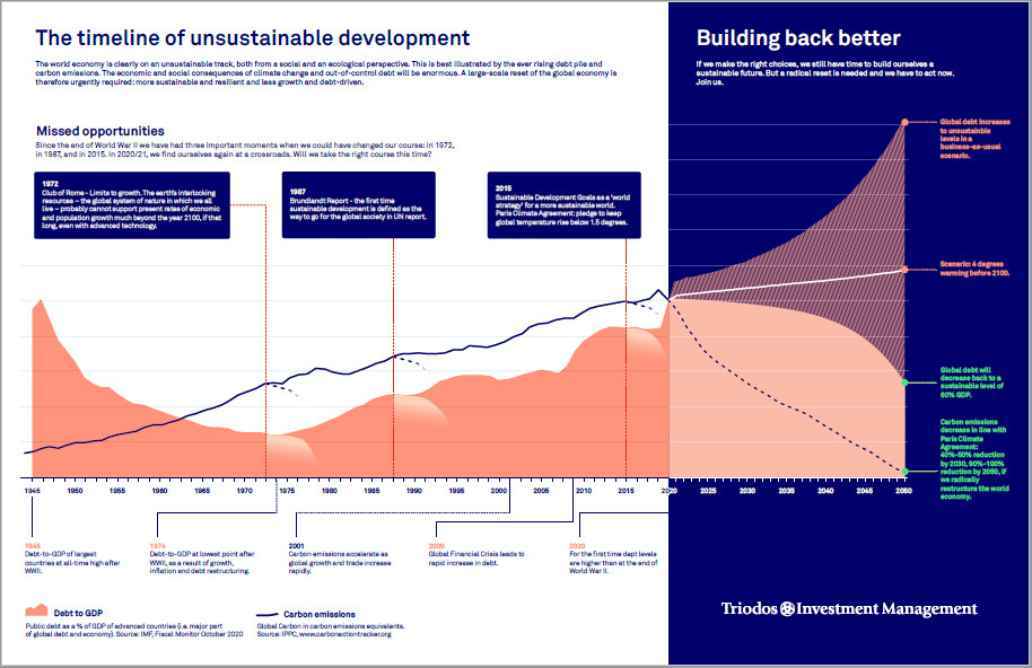

In May last year, we wrote that the COVID crisis points to substantial shortcomings in our current economic and social system and called for a reset of our economy. These shortcomings are certainly not new but are merely aggravated by the pandemic. The infographic shows the timeline of unsustainable development since the end of World War II. The pandemic and the period of lockdown gave us the opportunity, or rather the obligation, to redefine, revalue and redesign our economy, away from our growth addiction and our short-term thinking. The task at hand is to build back a better, more sustainable, and resilient economy.

Now that a year has passed, we can take stock of what has been achieved. On paper, it doesn’t altogether look bad. Policymakers have undeniably become more aware of the biggest problems of our time: because the US and China are now also displaying climate leadership, the chances of ‘Paris’ being reached have increased a little. The ambitious European Green Deal aims at a sustainable recovery, for which the EU has made a substantial amount of money available. Reality, however, paints a far less positive picture. Because it now looks as if the post-COVID recovery will be very carbon-intensive. It is also clear that only a very small part of public funds will be used to facilitate a green recovery.

Reset the economy - Investing in radical change

In the coming months, in a new series of articles and podcasts, we will explore the contours of such an economy, and the ways to get there. Join us in building the economy of the future.

What we do know for certain, a year after the outbreak of the COVID pandemic, is that the inequality in the economy has grown and resilience has diminished. The acute phase of the crisis as well as the vaccination process has further magnified the inequality between rich and poor countries: government funds allowed rich countries to better cushion the economic blow and these countries also had more means of buying large supplies of vaccine. At the same time, however, the resilience of most economies has deteriorated, as national debts have risen enormously.

Those high debt levels are also related to a second type of inequality: that between generations. Young people were unable to go to school for a long time and consequently suffered social and psychological distress, and on top of that they are also the ones who at some point in the future will be left to pay back the debt that we have taken on. Those that benefit from this (in relative terms) are the older generation: they were relatively spared by the lockdowns and are also not the ones who are going to be paying off those debts in the future.

We remain stuck in the paradigm of short-term economic growth and profit.

While the debt levels of governments and companies in sectors that were hit hard by the pandemic, such as the travel and leisure sector, have risen, there are also large groups of people who are actually much better off now: anyone who had assets has only seen their wealth increase in the past year. The largest companies – such as big tech – profited both from more demand for their services and the strong recovery on financial markets driven by extreme loose monetary policy. The ‘big tech’ companies have grown even bigger. This means that the financial world has disconnected further from the real economy, as a result of which the resilience of the economy has been reduced rather than enhanced.

Meanwhile, the relationship with nature has not become stronger; we have no idea how to limit our vulnerability to zoonoses jumping from animals to humans. On top of that, 2020 was also the year that started with huge forest fires and turned out to be the second warmest year in human history. The Dasgupta review on biodiversity, a comprehensive report on the economics of biodiversity that was commissioned by the UK Treasury, reconfirmed that the relationship between the economy and biodiversity can only really recover if we fundamentally change the way in which we treat nature: not as an input for our economic system, but as an asset as such. And therefore, also not as something that can be protected by putting a price on it, but by explicitly not marketing it.

This has highlighted once again that post-COVID we are still stuck in the paradigm of short-term economic growth and profit. If the economy does not grow or a company is not making a profit, we have only one reflex: save whatever we can by injecting more money into it. And we do this without first asking ourselves whether this actually creates any wealth in the longer term at all. At the same time, we have known for a long time that wellbeing is a much broader concept than just economic growth or profit.

So, the reset needs a reset. A reset that explicitly centres on the creation of wellbeing. That is what the next blog will be about. Keep following us on this page and via social media.

Investing in radical change

Download our vision paper and find out how you can contribute to the transition towards a more sustainable and resilient economy.