The world order seems fundamentally changed, with the US no longer serving as a cornerstone of free trade and democracy. Trump’s 'America First' policies have accelerated the decline in US global influence and stability, resulting in a more fragmented world. In this outlook, we assess the impact of this US-induced acceleration of global fragmentation. In four scenarios - one baseline and three alternatives - we explore the short-term economic impact and long-term climate consequences.

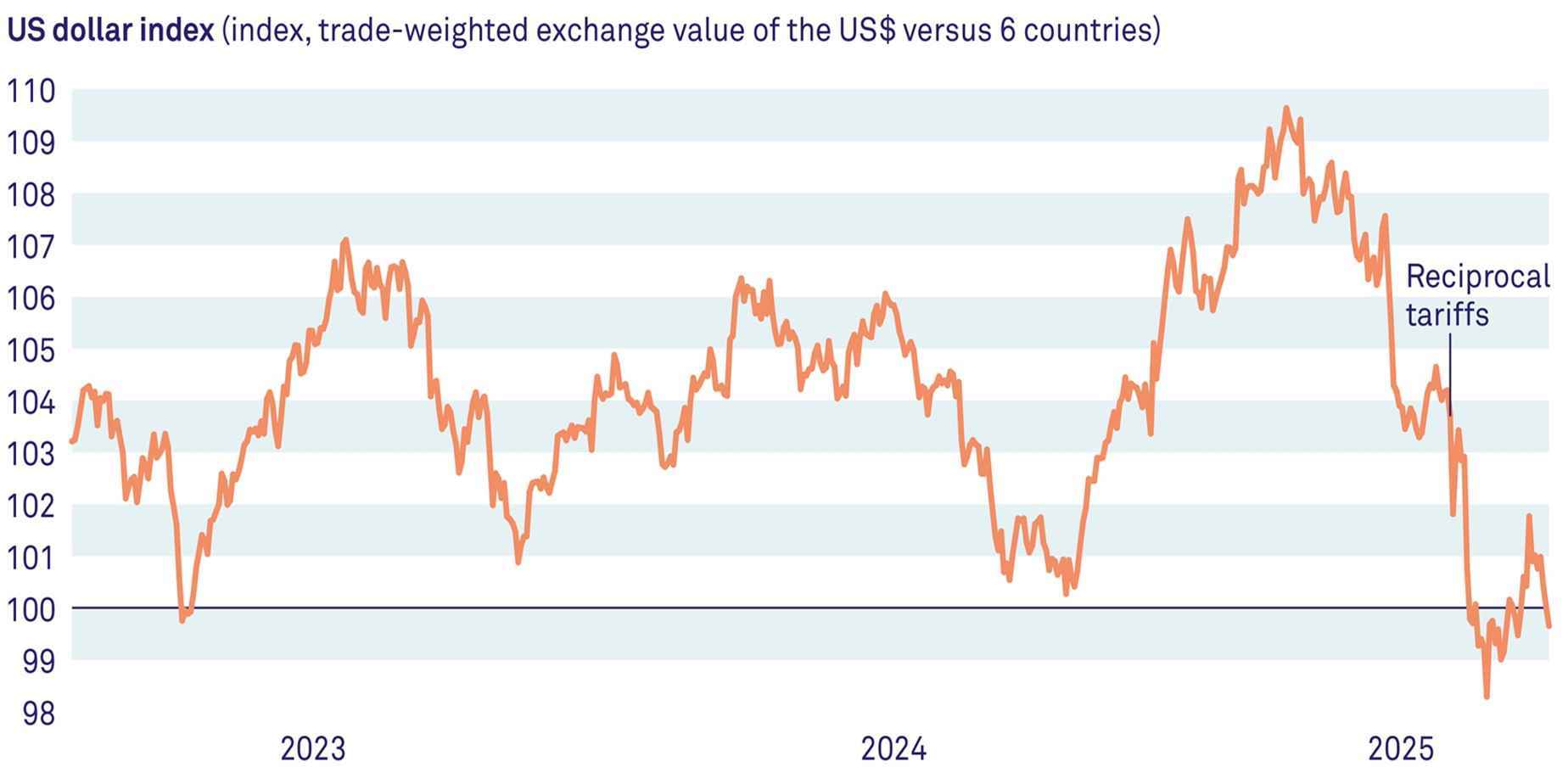

Ever since the inauguration of Donald Trump as the new president of the US, investors have endured a rollercoaster of emotions. The US tariffs introduced on 2 April, ironically labelled 'Liberation Day', sent shockwaves through financial markets. Aimed at protecting domestic industries and reshoring manufacturing, these measures marked a sharp turn toward economic nationalism. Trade tensions, particularly with China, escalated quickly, fuelling uncertainty and prompting concerns about US long-term stability, thereby increasing US borrowing costs.

A temporary pause in tariffs was later announced, and trade negotiations with several countries commenced. The UK and China struck a tentative deal with the US, though the announced tariff reductions remain entangled in a web of clauses, exemptions and ambiguity. Nonetheless, equity markets fiercely celebrated the tariff pause and trade deals by making up for all the losses since 2 April.

No turning back

Despite this investor relief, the notion of returning to pre-April 2nd conditions seems unrealistic. Global fragmentation was already underway, but Trump’s 'America First' agenda has significantly accelerated this trend. Even with tariffs partially rolled back, the post-World War II international order — in which the US was the cornerstone of free trade, NATO, and democratic norms anchored in the rule of law — has fundamentally changed. Underlying this is a broader transformation in US governance: a drift toward more autocratic tendencies, exemplified by the rollback of climate policy, for instance by the decision to largely disregard the economic cost of climate change as it sets policies and regulations.

The still elevated price of gold and weakened US dollar are clear signals of persistent global uncertainty and waning confidence in the US's leadership role.

Still, the US is the dominant force in the global financial system: it accounts for 40% of the bond market, over 50% of equity market capitalisation, and the US dollar functions as the global reserve currency. Given the current erratic policies, this dominance suggests that heightened market volatility, currency fluctuations and capital flight (out of the US) may become recurring themes in the new geopolitical context. This does not mean, however, that equity markets can’t continue to rise; history has learned investors are short-sighted. De-escalation for now seems to be enough, even though we are likely heading toward a less favourable equilibrium.

- Baseline: de-escalating into a more fragmented world

In our baseline scenario, we assume a de-escalation in the trade war. Nevertheless, the world will end up with significantly higher trade barriers than before, with a 10% US universal tariff and for China even 30%. Retaliation will be relatively modest. Distrust in the US will result in lower overall confidence levels, facilitating global power games by authoritarian regimes. The result is a more fragmented world and more limited multilateral cooperation.

In this fragmented world, we assume delayed and divergent climate policy ambitions globally*. The EU and the UK will likely reach net zero CO₂-emissions by 2050, as they aim to increase global competitiveness and become less dependent on (semi) autocratic regimes for their energy and resource supply. This is also why they live up to their announced government investment in defence and (green) infrastructure. We expect China to live up to its climate pledges made so far, but this by far does not equal net zero by 2050.

- Trade escalation: Liberation Day

In this scenario, tensions build again, resulting in the eventual implementation of the US reciprocal tariffs and an even higher tariff rate for China in the second half of 2025. US trading partners retaliate. Tensions within Europe resurface as countries prefer near-term domestic economic support measures, partly limiting government investment in defence and infrastructure. This scenario also assumes delayed and divergent climate policy ambitions globally, but assumes both the EU and UK will still live up to all their climate pledges**.

- Trade escalation: global race to the bottom

In this scenario, trade tensions build even more, especially between the US and China. The result is a 145% tariff on Chinese goods, and a 125% retaliatory tariff on US goods. Other US reciprocal tariffs are also upped by 15%, which results in higher retaliatory tariffs as well. The EU and the UK revert to domestic short-termism and abandon their investment in defence and (green) infrastructure. This scenario also assumes delayed and divergent climate policy ambitions globally, but assumes that the US and China stick to current climate policies in a competitive fossil fuel-driven race to the bottom**.

- New hope: strategic partnerships and climate action

Trade war de-escalation is combined with the formation and/or strengthening of strategic bilateral trade partnerships and broader trade coalitions not dominated by the US. The US 10% universal tariff and 30% China tariff are still in place, but only China retaliates. As a result, the global confidence shock evaporates rather quickly, and global trade finds new ways and is hardly impacted. EU and UK planned government investment in defence and (green) infrastructure materialises, as there is still a sense of urgency to become strategically independent from the US.

However, the US-induced acceleration of fragmentation, on top of the lingering global distrust related to power games of authoritarian regimes, still prevents countries to cooperate fully when it comes to climate. Therefore, this scenario assumes that climate ambitions in general will remain as moderate and heterogeneous as they were at the beginning of 2024 in the coming decades**. We nevertheless expect the EU, the UK and China to reach net zero by 2050, as this suits their strategic ambitions. The US will eventually step up its climate efforts as well (after 2030), reaching net zero in 2050, as it does not want to be left behind in the green technology race***.

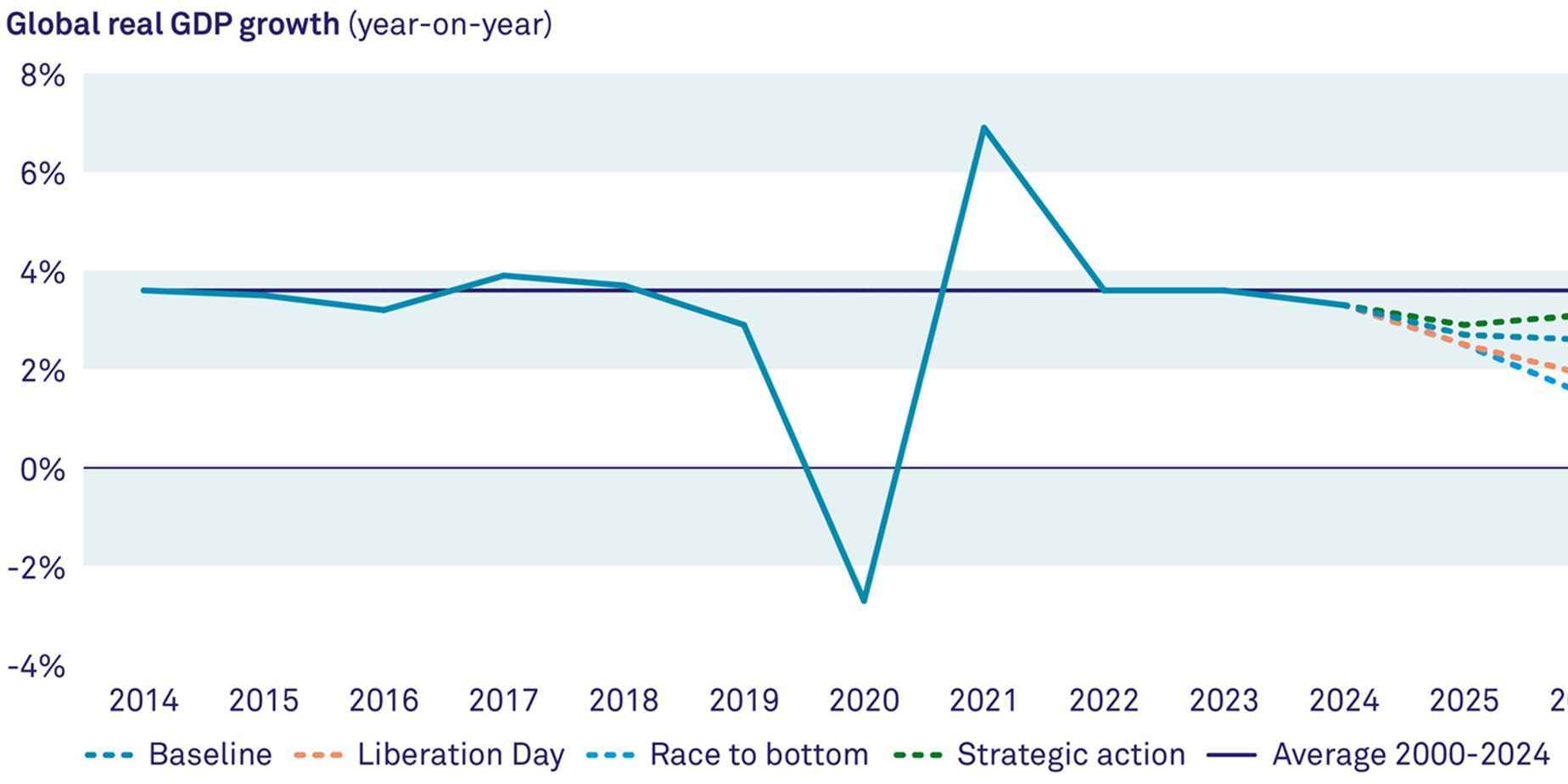

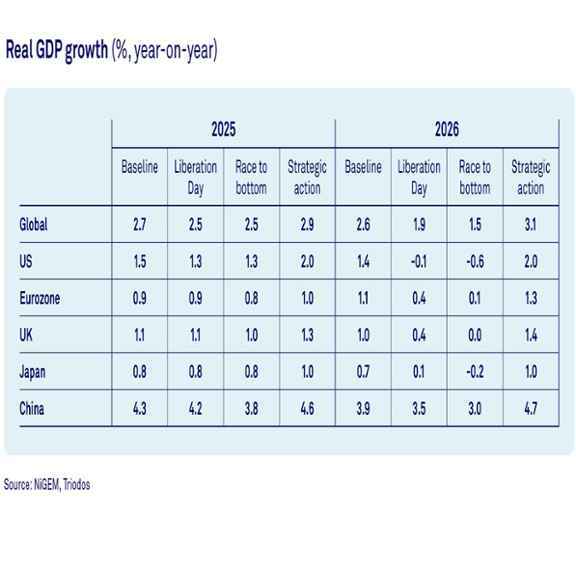

Results: lower global growth, but no local recessions in baseline

Our scenario analysis suggests a significant impact of the US tariffs and global confidence shock that will mostly materialise in the second half of 2025 and in 2026. As a result, in our baseline global economic growth will be just 2.6% in both 2025 and 2026.

The US will likely not fall into a recession, but US business investment is hampered by the ongoing uncertainty. The short-term impact on eurozone and UK economic activity is relatively modest in the baseline. In the two escalation scenarios, the US and China both fall into a recession, mostly driven by sharply contracting business investment in combination with deteriorating household consumption. The eurozone, UK and Japan only experience a recession in the ‘race to the bottom’ scenario. In the strategic action scenario, global growth is not materially impacted.

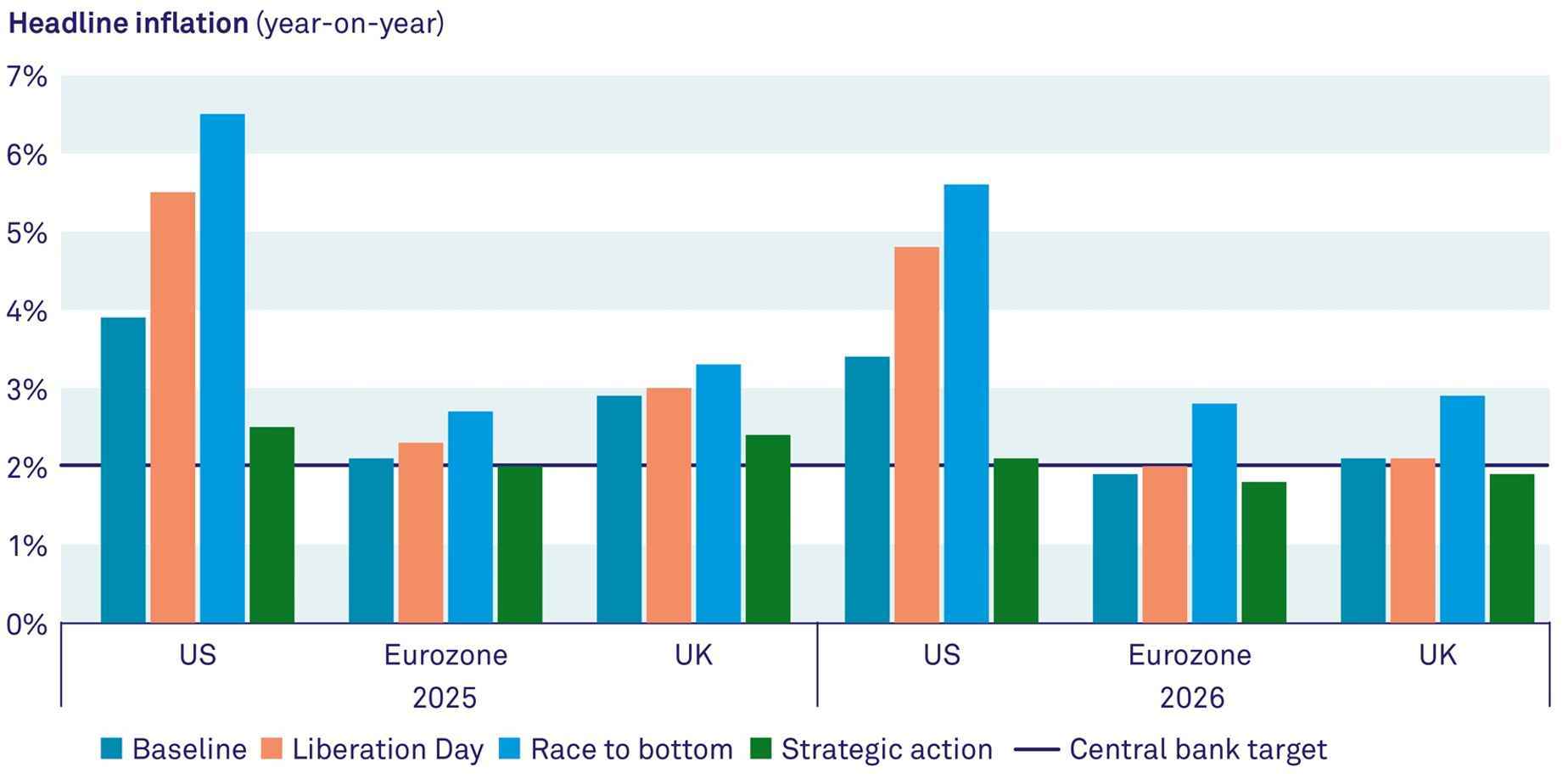

When looking at headline inflation, the scenario analysis clearly shows that the tariff increases significantly push up US consumer prices in the baseline and both escalation scenarios, thereby reducing household disposable income and thus consumption. Eurozone and UK inflation is only materially impacted in the ‘race to the bottom’ scenario, although in that case Chinese dumping of goods intended for the US markets prevents a more significant inflationary impulse.

Concluding, it is clear that the move towards more fragmentation has repercussions for global growth, even when the trade war de-escalates. The US will be the most impacted in the baseline, whereas the short-term economic impact on other advanced economies is not of worrisome proportions.

Federal Reserve faces difficult trade-off

The new US trade policy has put the Federal Reserve in a difficult position: defend the economy or contain inflation? Based upon our baseline results, which point to elevated price pressure, and comments made by Fed chair Powell that hint at a stronger focus on inflationary pressures than growth concerns, we expect only two 25bps rate cuts until mid-2026, with the policy rate ending up at 3.75%-4.00%.

For the ECB and the BoE, the new situation is more clear: there is a modest negative impact on economic growth in the baseline, while inflationary pressures do not increase. This means we expect three 25bps rate cuts by both until mid-2026, meaning their policy rates will end up at 1.5% and 3.5%, respectively.

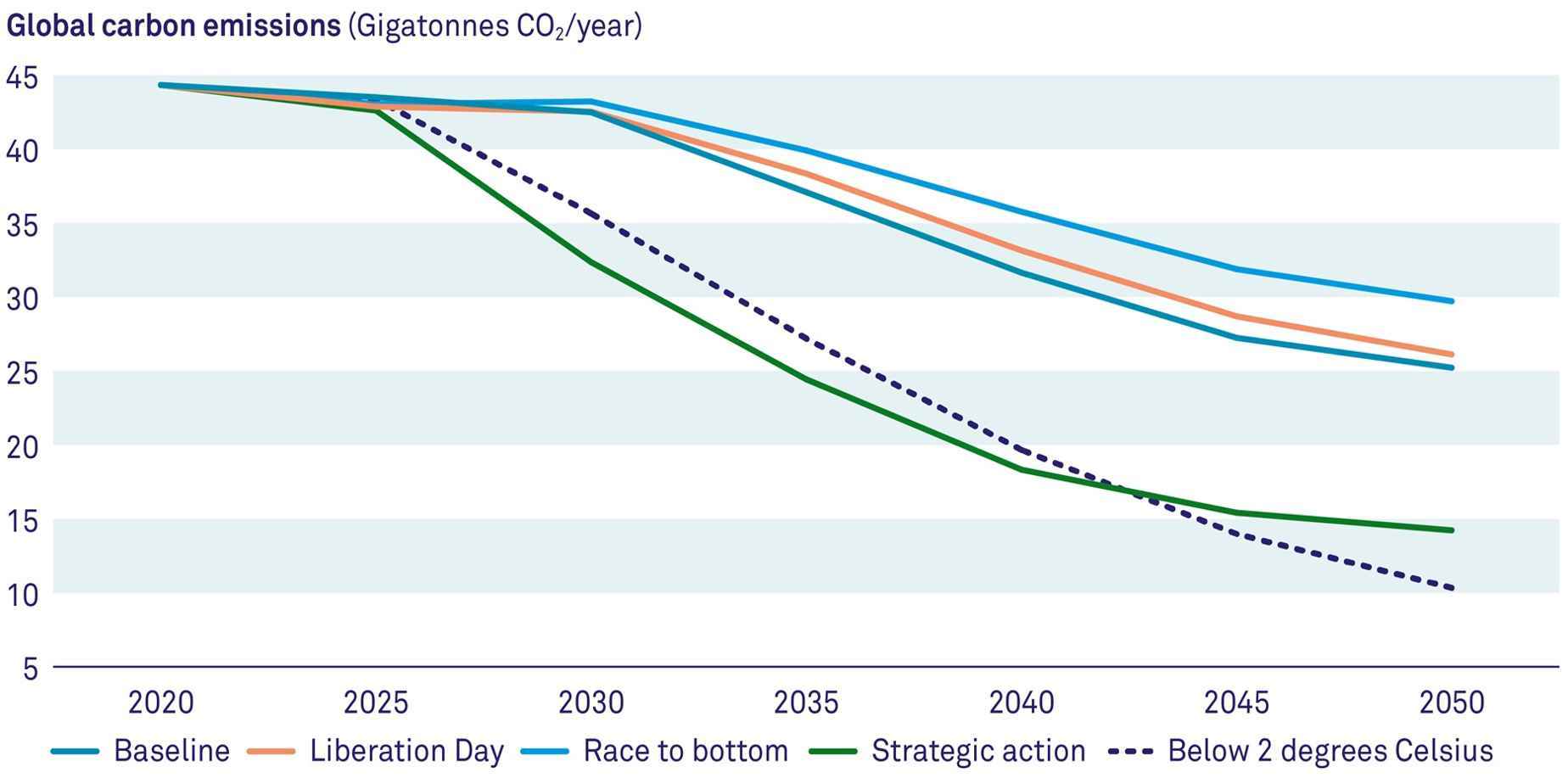

Fragmentation always limits climate action

When focusing on the long-term climate impact, it is clear that even in the scenario that assumes an increase in strategic partnerships and climate action, the world fails to keep the global temperature rise below 2 degrees Celsius, let alone 1.5 degrees. The US-induced acceleration of global fragmentation thus has far-reaching climate consequences, as some countries’ ambitious efforts will be undermined by limited action in others. This is in line with a new study that finds that immediate universal action is required, as even with targeted interventions, several planetary boundaries, including climate change, will remain transgressed in 2050.

Interestingly, the difference in carbon emissions between our baseline and the ‘Liberation Day’ escalation scenario is limited, indicating that the eventual size of the tariff rates is not decisive for global emissions. Rather, it is the increase in distrust between countries and the subsequent decrease in global cooperation that is decisive. Even when the EU, UK, China and after several years the US step up their climate efforts so that they reach net zero in 2050, this will not limit global warming to below 2 degrees Celsius. This underscores the need to revive global cooperation to address shared challenges.