This sharply contrasts with the extended rally in financial markets since the end of March, which suggests the global economy is heading for a smooth, V-shaped recovery. We still expect the superhuman monetary powers, which have inflated asset prices, to wane and the monetary injections to dry up eventually, forcing investors to face reality. In the meantime, we hope fiscal policy makers, especially in Europe, will strengthen their economic policy agenda to create a more sustainable economic system.

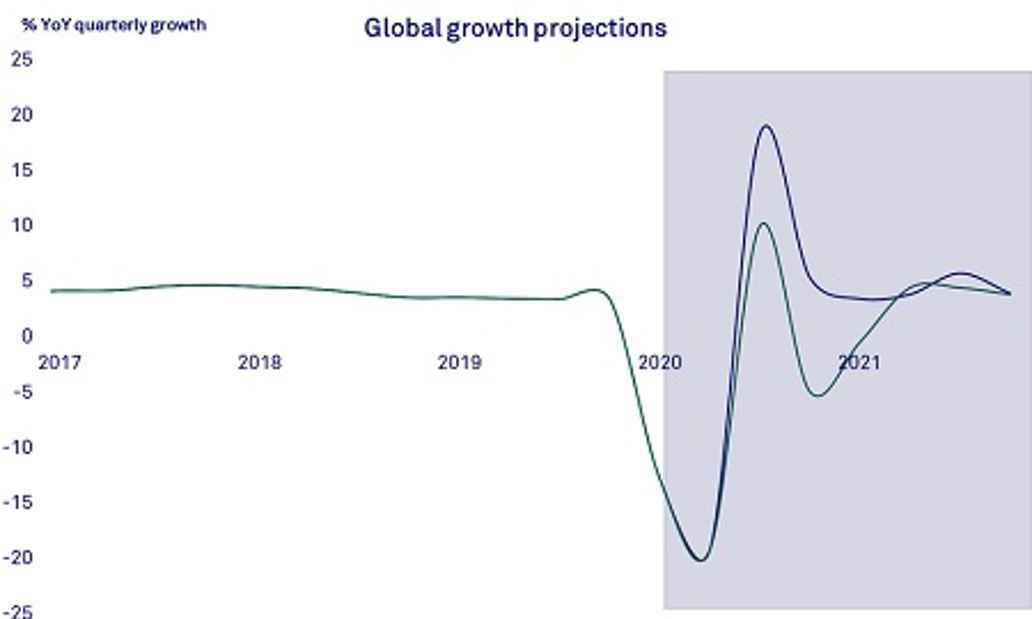

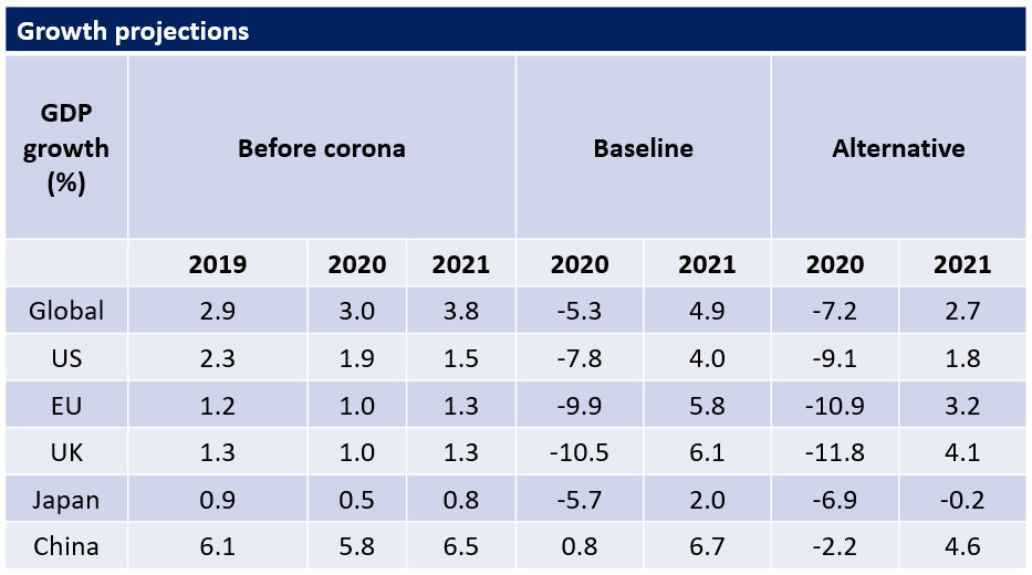

In our 2020 baseline scenario, we project a global economic contraction of 5.3%. We expect that recurring localised lockdowns and persistent uncertainty will hamper the economic recovery. Our more pessimistic alternative scenario projects a global economic contraction of 7.2% for 2020. In this scenario, we assume a return to large-scale virus outbreaks starting in the fall of 2020. In both scenarios, the coronavirus pandemic is causing economic damage that our current economic system will be unable to heal, leaving permanent scars. A fundamental reset of our economy is therefore necessary to make the system more resilient and sustainable.

A swift, full-blown economic recovery as expected by financial markets is unlikely, despite the unparalleled fiscal and monetary stimulus. Macroeconomic indicators and corporate earnings will significantly improve from their bottom-lows, but there will be no catch-up effects, implying a permanent output loss for the global economy. The growing discrepancy between financial markets and the real economy will ultimately lead to some form of reality check, although the current situation may continue for quite some time. Based on our fundamental approach, we maintain our cautious stance and remain underweight in equities and neutral in bonds.

Deep and persistent recession

Our latest economic growth projections are based upon two scenarios:

- In our baseline scenario, we expect an annual economic growth rate of -5.3% in 2020 and 4.9% in 2021. The virus will continue to roam around for the remainder of 2020, with a vaccine only becoming globally available in the course of 2021. This results in recurring localised lockdowns, which will prevent a complete resumption of economic activity. Economic recovery in 2021 will be slow, as some restrictive measures may still be in place and the downside economic effects of this recession will also come into play. At the same time, uncertainty about longer-term fiscal policies remains. In this baseline scenario, the eurozone and the UK will be severely hit in 2020, while the US and Japan will experience relatively low annual growth rates in 2021.

- Our alternative scenario assumes an annual economic growth rate of -7.2% in 2020 and 2.7% 2021. Renewed large-scale virus outbreaks in the fall of 2020 require the reimplementation of national lockdown measures. A vaccine will become globally available later in 2021. In this scenario, economic recovery will not only be slow, but also start later in 2021. Again, the eurozone and the UK will be severely hit in 2020. The US and Japan will experience relatively low annual growth rates in 2021.

Unwarranted optimism

The financial markets’ freefall after the global outbreak of Covid-19 was followed by a strong rebound that started end of March, and a further upward move that stretched until the beginning of June. During this period, investor sentiment was lifted by unprecedented global monetary and fiscal stimulus, declining numbers of newly reported coronavirus cases in most of the Western world and the (partial) reopening of several major economies. In June, however, worries about a pause in the easing of lockdown measures or even renewed lockdowns emerged, slowing the upward trend in equity markets.The main global concern was the situation in the US, where a rapid spreading of the virus forced several states to postpone or reverse their reopening plans.

Government bond yields remained essentially flat during the quarter, while corporate yields decreased due to the combined increase in risk appetite and central bank stimulus. Oil markets recovered from April’s crash, as oil demand showed signs of picking up and the agreed supply cuts by OPEC and some other countries began to take effect.

We deem last quarter’s extreme investor optimism unwarranted for two reasons:

1. Corona is far from over

At the end of June, more than 10 million coronavirus cases had been recorded worldwide, with over 500,000 fatalities. Although several countries in Western Europe and Asia seem to have the virus under some degree of control, globally the number of new cases is accelerating. The World Health Organisation recently expressed fears that the worst is yet to come. Indeed, without a vaccine becoming globally available anytime soon, we foresee months with recurring infection spikes that will require periods of localised lockdowns.

2. The global economy is nowhere near pre-corona levels

- Recent upbeat economic data is misleading

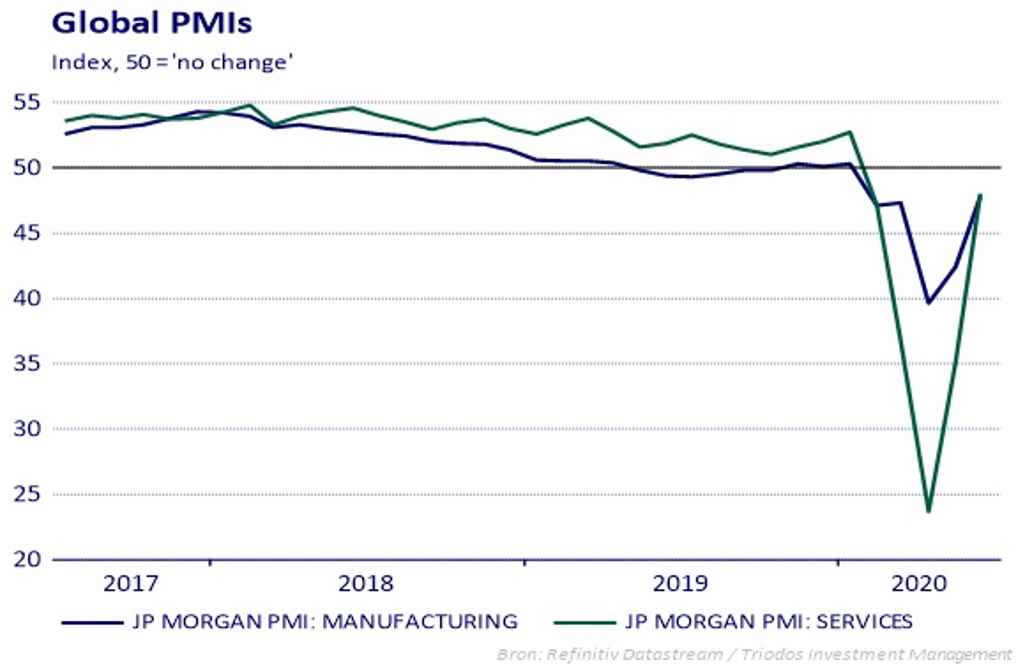

The pick-up in economic activity following the gradual lifting of the lockdown measures has triggered investor enthusiasm. Indeed, most economic indicators bottomed in April during the peak of the lockdown measures and improved in May and June. However, most monthly or quarterly gains only mean that the trough in economic activity is behind us (case in point are the global PMIs, which show a V-shaped recovery but are still below 50, indicating contraction compared to the previous month). We are still nowhere near pre-corona activity levels, although recently published V-shaped graphs suggest otherwise. Recurring localised lockdown measures will prevent a complete resumption of activity for quite some time. In addition, the negative effects of, for example, weak consumer demand and low business investments will materialise at a later stage and may then cause severe feedback loops.

- Earnings expectations are unrealistic

The quick and full economic recovery that financial markets have priced in, has yet to materialise in company earnings. In the US, for instance, the consensus expects a decrease in earnings per share (EPS) of only 12% this year, followed by a 29% gain in 2021. This means that earnings will have to fully recover from their freefall by the end of the second quarter of 2021. However, given the above considerations, and the consensus that US economic activity will not return to pre-crisis levels until at least early 2022, this seems impossible. According to a recent survey by the Business Roundtable, more than a quarter of the CEOs of US companies do not expect a recovery for their companies until after 2021.

Considering the above, it is highly unlikely that the global economy will see a smooth V-shaped recovery, as is currently priced in by financial markets. Even if countries have learned from their previous experience and deal with second coronavirus waves locally, in combination with continued general precautionary measures this still means that global economic activity can’t shift into full gear for a long time, meaning pre-corona levels are out of reach.

Permanent scars

We expect the economic recovery to materialise at an even slower pace than we initially anticipated, and we foresee permanent changes caused by the coronavirus crisis. These will result in lower global growth potential. According to the IMF, the corona-related cumulative output loss to the global economy during 2020-21 will be approximately USD 12.5 trillion. This means that economic growth in 2021 would be 6.5 percentage points lower than in the pre-COVID-19 projections by the IMF made in January 2020.

Three main features of the current pandemic will likely cause more permanent economic scars than would normally happen during recessions:

- Lasting weak demand

The nature of this pandemic-related economic crisis causes greater and more prolonged uncertainty than usual during other recessions. This uncertainty, in turn, results in very low confidence of both consumers and businesses. Lack of confidence usually translates into lower spending. Prolonged uncertainty could well lead to more permanent changes in spending patterns, i.e. weaker demand from both consumers and business.

These developments amplify a trend that has presumedly existed long before the coronavirus emerged: secular stagnation, i.e. a chronic lack in demand. In this theory, ageing populations and a lack of investment opportunities due to waning technological innovation result in too much saving and too little investment, creating structurally lower economic growth.

- Erosion of human capital and the workforce

The lockdown measures also include schools and universities. This may impact the long-term quality of the education of the workforce, leading to a lasting erosion of human capital. Job losses due to lockdown measures have also been massive. In part, this is a consequence of our current economic system’s preference for flexible labour markets. In the end, the longer people are unemployed, the more skills and expertise will be lost permanently. It is unlikely that all laid-off workers will find their way back to the workforce, leading to a permanent reduction in the workforce.

- Deglobalisation

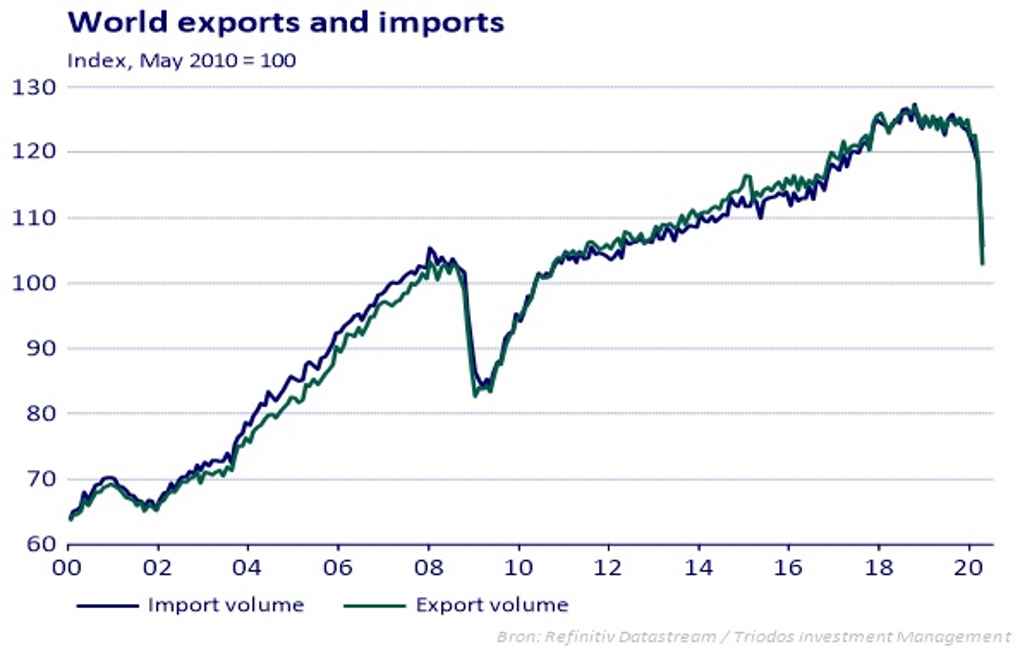

The growth of the world economy over the last decades was mainly based on the ongoing globalisation. However, world trade data indicates that after October 2018, global imports and exports are in a downward trend. Geopolitical tensions, for instance between the US and China and the UK and the EU, have led to trade barriers and interrupted supply chains. The coronavirus crisis is likely to accelerate this trend, as governments have become aware of the downside risks of not being able to produce vital products locally. Companies have become aware of the trade-off between efficiency and resilience. Tensions between countries have also further built up. This will likely accelerate the deglobalisation trend long after the virus has been brought under control. This is not an unfavourable development. It is essential to increase the resilience and sustainability of our economic system, for instance through more local production.

Consumer price inflation likely to remain low

Much of the discussion on the implications of the unprecedented monetary and fiscal stimulus packages has focused on inflation, and rightfully so: traditional macroeconomic theory suggests that an increase in the supply of money (M) normally leads to a proportional change in the rate of consumer price inflation (a price change in the average consumption of goods and services by households). Since more than ten years, however, this transfer mechanism does not seem to work anymore. During the same period, a significant increase in (financial) asset prices (e.g. equities and houses) did materialise. In the short to medium term, we do not expect a sudden reversion of these trends, as the current pandemic and related economic recession will only exacerbate the effects causing low inflation:

- The prolonged period of uncertainty and continued restrictive measures will lead to lasting weak demand, which will overshadow any supply shortages in the coming months. Households will prefer to hold significant amounts of savings and business will stall investments, creating structurally lower economic growth;

- Human capital erosion and a prolonged period of high unemployment (leading to a reduction of the workforce) will not lead to any additional wage pressure;

- Increased inequality due to the economic recession will also decrease the labour share of income, putting a further break on any potential pressure leading to consumer price inflation.

There are three main forces that could possibly catalyse consumer price inflation in the longer term:

- The predicted de-globalisation may lead to cost increases, as cheap labour and efficient supply chains (partly) disappear;

- Integration of fiscal and monetary policies would help to have the created money actually flow into the real economy;

- A confidence crisis in the current monetary system, both as a cause and a result of a revaluation of the effectiveness of current central bank policies.

For the time being, the forces putting downward pressure on consumer price inflation will dominate. Current inflation expectations confirm this general assumption. The long-term inflation outlook remains highly uncertain.

A sustainable reset is the only way forward

The issues described above show that the economic recovery from the coronavirus crisis will be slow and incomplete. Worrying pre-corona trends such as low productivity growth and low inflation are likely to be exacerbated. According to the IMF the negative impact on low-income households will significantly raise inequality and therefore increase poverty. On the one hand, this threatens the global economy as we know it. On the other, it offers the opportunity to reset our fragile economic system in a way that would not have been possible if the economic recovery would have been stronger. Now is the time to achieve a more robust, sustainable and inclusive economic system.

Monetary and fiscal policy makers should follow an investment agenda that supports the transition towards a more sustainable economy. In Europe, the focus should be on a coordinated swift implementation and execution of the European Green Deal, that could serve as an example for the rest the world. Globally, there should be a renewed focus on the fulfilment of the Sustainable Development Goals in the next ten years. The recently published Sustainable Development Report 2020 shows that the coronavirus crisis is leading to ‘a significant setback for the world’s ambition to achieve the SDGs, in particular for poor countries and population groups.’ Progress in achieving the SDGs was too slow even before the corona outbreak, so the current situation asks for an unparalleled global cooperation. The outcome of the upcoming US presidential elections is one of the key events that will determine whether this will be possible.

Cautious stance

The gradual further reopening of economies means activity can pick up in the next couple of months, thereby generate positive quarterly global economic growth rates. Looking past the coming quarter, we expect that persistent weakness of demand likely means global GDP will not return to its pre-virus growth path for a long time. Therefore, we expect that monetary and fiscal support will remain extremely accommodative, with central banks eventually reaching the limits of their options.

The pandemic has triggered a massive disruption of the global economy. ‘Safe haven’ government bond yields remain near historical lows. Hence, their return potential is low. At the same time, corporate bond yields have gone down last quarter after moving up sharply during March. However, both investment-grade and high-yield credits are still above their pre-corona levels, making the valuation of corporate credit still relative attractive compared to government bonds. Besides, credits are likely to benefit from policy measures aimed at improving liquidity and solvency. For this reason, we slightly increase our exposure to investment-grade credits. We prefer high quality names, as the collapse in economic activity is triggering a rise in downgrades. Overall, we remain broadly neutral in our fixed income allocation.

We remain prudent on equities and do not chase the rally. Equity valuations have again increased due to the strong market rebound. The US equity market continues to look expensive on a variety of metrics, both relative to other regions and from a historical perspective. European and Asian markets, including Japan, look cheap relative to the US. Earnings estimates have come down, but current expectations are still relatively high. Negative earnings surprises are in the cards, in which case lower equity prices and valuations would be entirely warranted. Current equity price developments seem too much and too soon. Current valuations do not properly reflect underlying fundamentals, whereas central banks cannot be assumed to continue supporting asset prices indefinitely. We therefore remain underweight equities.

The return of transitions

Also read our long-term economic outlook The return of transitions. This outlook reflects our investment philosophy. It is the basis of the strategic asset allocation for our impact equity and bond funds.