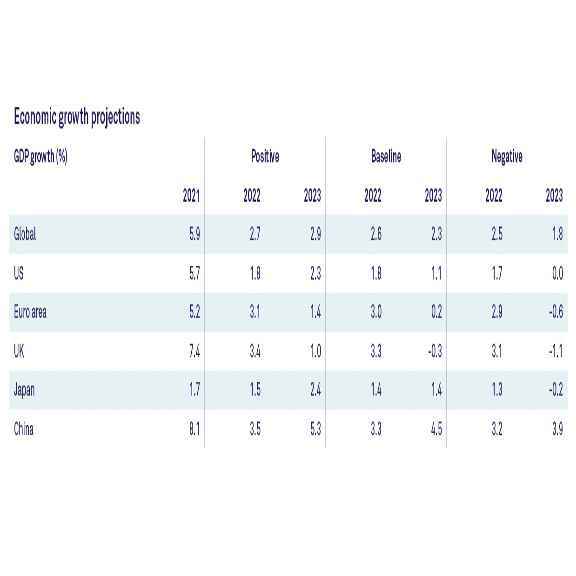

Regional recession risks have continued to increase, as Russia has cut its Nordstream-1 gas supplies to Europe, inflationary pressures have broadened across advanced economies, and most major central banks have upped the stakes by committing to more aggressive and prolonged tightening. In our baseline scenario, the eurozone and UK have (almost) entered recessionary territory. In our negative scenario, further upside inflation surprises will also tip the US and Japan into a recession, although a global recession will still be avoided. In our positive scenario, which we still deem least likely, inflation would come down faster than expected due to quickly fading supply constraints. The eurozone would in that case narrowly avoid a recession.

Strong labour markets have supported consumption

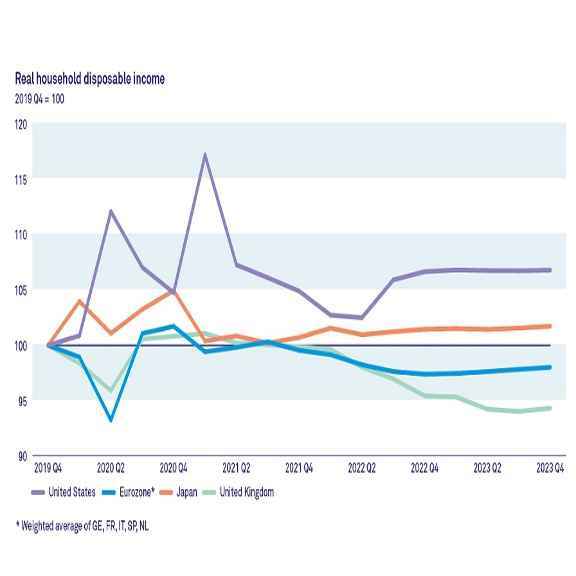

Wellbeing has been under increasing pressure across advanced economies due to sharp price rises since the end of last year. Lower-income households had to cut their spending as their disposable income became insufficient to cover their regular expenses. This has increased poverty and inequality. However, so far, aggregate advanced economy private consumption growth has merely slowed. An important reason for this resilience is that total real household disposable incomes have not fallen of a cliff, despite the record-high inflation: strong labour market recoveries after the COVID-recession have resulted in additional national income. On top of that, COVID-19 reopening effects (Europe, Japan) and the deployment of huge excess savings that have been built up since the start of the pandemic (US) have played their part.

European recession ahead

Going forward, the evolvement of private consumption remains key for the prospects of the major advanced economies. Therefore, real household disposable income and the willingness to spend excess savings will decide their economic faith. The main factors determining real household disposable income are inflation, labour market dynamics, and fiscal policy. The outlook for these key determinants varies across the major advanced economies:

- Inflation: In the US, headline inflation has likely peaked during summer, and limited yearly rises in energy prices imply a continued gradual fall going forward. Although we expect it to remain above the Federal Reserve’s target for at least the next twelve months, inflation will weigh less heavily on disposable income. For the UK and the eurozone, however, the Russian gas supply cuts imply that headline inflation will not peak before the final quarter of the year, meaning inflation will continue to negatively affect disposable income. The UK will, on top of that, experience additional inflationary pressures because of Brexit. Japanese inflation will also peak towards the end of the year, but due to strong country-specific disinflationary dynamics at much lower levels.

- Labour market: Labour markets are exceptionally strong in all major advanced economies, but their relative strength varies: The US labour market is red hot, with around two vacancies per unemployed person. In Japan, this ratio is 1.3 to 1, in the UK 1 to 1 and in the eurozone 0.3 to 1. Going forward, the favourable vacancy ratios in the US and Japan bode well for continued near-term labour market strength and thus national disposable income, as the excess vacancies provide a partial buffer before any cooling of demand starts to increase unemployment. In that respect, the eurozone and UK are more vulnerable to cooling demand.So far, wages have been growing fast in the UK and especially the US (though not as fast as inflation), partly because of the more flexible labour market structure compared to the eurozone. Therefore, we expect some catching up in the eurozone, but this will be limited as labour markets are relatively less tight. Falling inflation in the US and relatively modest inflation in Japan should moderate wage growth in both countries.

- Fiscal policy:The governments of the major advanced economies have stepped in to support their citizens, with a variety of measures such as (energy) price caps, cash handouts and windfall taxes. This will lower inflation and support economic growth. Eurozone support is equivalent to 4% of GDP and US support equal around 3%. However, the recent plans of the UK’s new government push UK fiscal support to around 9% of GDP. This is dangerous, as it is likely to spur medium-term inflation. The plans are also highly controversial, as they include tax cuts for corporations and high earners.

Combined, these factors point to continued near-term private consumption resilience in the US and Japan, while deteriorating real household disposable income should lower private consumption in the UK and the eurozone. We expect that these effects have already pushed the UK into recessionary territory in Q3 and that the eurozone will follow suit in the final quarter of the year. Uncertainty due to the gloomy outlook will likely prevent European households from dipping deep into their excess savings to compensate for the loss in purchasing power.

These factors also determine our monetary policy expectations: in the US, the combination of above-target inflation, a red-hot labour market and near-term growth resilience implies continued aggressive tightening, in line with current market expectations. However, while we expect the European Central Bank and the Bank of England (BoE) to also continue with their tightening efforts, our call is for lower peak policy interest rates than markets have priced in. We expect European central bankers to increasingly focus on growth concerns and financial stability. That said, the latest inflationary fiscal plans in the UK may force the BoE to be more aggressive. Overall, our expectations for rising interest rates, slowing demand, and continued uncertainty (inflation, war) also do not bode well for private investments and international trade.

Wellbeing number one priority

Ultimately, the end-goal of governments should be to improve wellbeing, which of course does not equal improving economic growth. Using real household disposable income per capita as a proxy for material wellbeing, our dismal growth forecasts for the UK and the eurozone are in fact underestimating the impact on material wellbeing of the average European household. This is also the case in the US, where the growth slowdown is understating the impact on the average household’s material wellbeing. In contrast, material wellbeing of the average Japanese household improves more than our growth estimates suggest.

It is well-known that lower income groups are disproportionately impacted by the current surge in inflation. This therefore calls for targeted support from governments, not the broad-based measures that have so far been announced. In addition, it is key that governments realise there is more to wellbeing than disposable income. A more sustainable and socially just society could significantly improve wellbeing, even if economic growth remains subdued. Governments should therefore use this crisis to focus on accelerating the energy transition and reshaping our economic system in such a way that it becomes less dependent on growth. It is in that respect promising that all major advanced economies have taken significant sustainable steps, such as the EU’s REPowerEU plan and the recent US Inflation Reduction Act. But short-term measures still prevail, case in point being the expensive energy price caps that fail to stimulate energy efficiency. Governments would be wise to instead focus on durable clean energy solutions, so that the wellbeing of future generations is also secured.