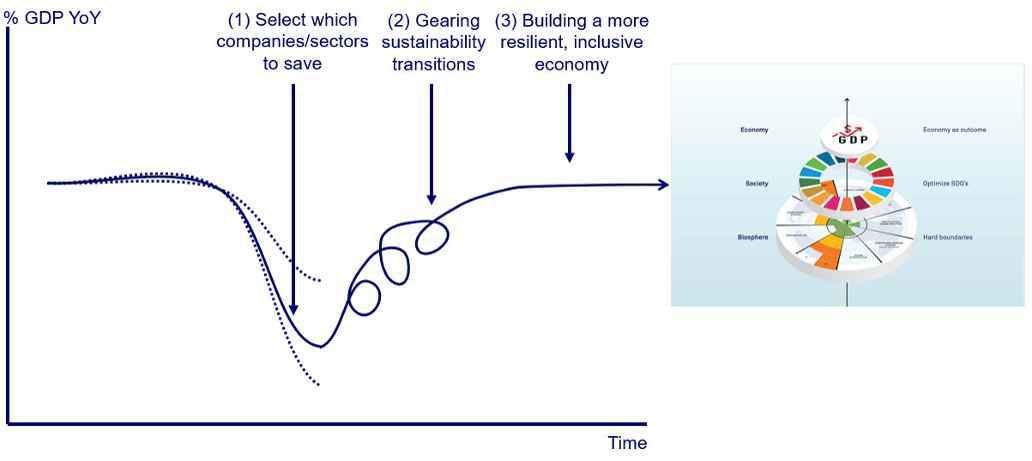

We simply can’t afford to put seemingly less urgent matters such as climate change, biodiversity loss and growing inequality on hold. How can we best achieve a more robust, sustainable and inclusive economic system? Bottom line: we need to choose what is worth saving from our current system, gear up sustainability transitions, and build a more resilient, sustainable economy.

A severe crisis…

The severity of the social and economic consequences of this health crisis can hardly be underestimated. Shutting down entire industries for what will likely be several months has dramatic effects on corporate profits, balance sheets, liquidity, employment, investment decisions and inequality. A significant drop in economic activity, which in some countries could be temporarily as high as 30% (!), is very hard to digest for the global economy. Feedback loops in the real economy and the financial system, such as capital flight, supply-demand interactions and contagion via increased risk premiums, aggravate this shock also to countries that are less directly impacted by the corona outbreak. A synchronic and symmetric shock of this size is unprecedented in modern history. Even the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 or the Great Depression of the 1930s were merely local (primarily Western) phenomena, in which for instance China and most emerging markets were affected in their domestic markets only to a very limited extent.

As highlighted in our previous update, global growth projections range from -1.5% to -7.2% in our scenarios, with poorer regions getting hit harder by the effects of this crisis in terms of inequality, capital flight and the negative effects of a global value chain crunch. This value chain crunch implies that because of demand fallout, production orders are canceled. Without good governance, this often results in low-income countries seeing their economic activities suddenly stop, because they strongly depend on those international value chains.

Although fiscal spending and accommodative monetary policies try to dampen the direct impact of the demand fallout, it is unlikely that this will be enough. Even if the containment measures, after the initial lock-down period, may be eased somewhat, they will still drastically limit economic activities. All in all, it might seem that the direct effects of the corona-crisis on economic activity will only truly disappear after a vaccine is found, probably by the end of this year.

This is also why we expect that, despite current developments, the equity bear market will get a next episode. As a rule of thumb, stock markets fall roughly as much as corporate earnings do. The depth and extent of this global crisis indicate that earnings should fall at least by some 50%. Most indices have by far not adjusted to that level yet.

…with long-lasting effects on economy and society

So far, we have only considered the immediate effects of the crisis on the economy. However, there are also longer lasting effects, both economically and socially, most of which related to the inherent fragility of our system, as highlighted in our previous update.

In economic terms, a few things stand out. First, we will probably end up with a lot more debt than we already had. According to estimates of the IMF, public debt will surge to close to 100% of global GDP this year, where advanced economies are expecting to see their gross public debts increase to 132% of GDP (increase of almost 20%-points) and emerging economies will see their gross public debt rise with almost 9%-points of GDP to 62%. For some countries, especially in emerging markets, debt maintenance will be a serious challenge going forward. Also, for companies, which from a historic perspective often have highly leveraged balance sheets, the debt burden might become a problem. We may end in a vicious circle of sluggish recovery resulting from a global debt-deflation overhang, with an increasing number of zombie companies, low effective demand and in the end structurally lower growth, making debt repayment even more difficult.

In addition to that, global monetary policy is more accommodative than ever before. Almost all central banks have slashed their policy rates, and major central banks are once more back to the so-called zero-lower bound – a short-term nominal interest rate at or close to 0%. The past few weeks have shown that using central banks’ balance sheets to buy whatever asset class is in trouble is becoming the ‘new normal’ for monetary authorities. The scary thing is that nobody knows when and how to stop this ballooning of central banks’ balance sheets. Worse, everyone suspects that the next step will even be further down the rocky road, in the direction of monetary financing. And although we are not against monetary financing – on the contrary, it can definitely work to alleviate debt and bring money to the real economy – the instrument should be used carefully for the real economy and not to infuse more money in the financial system without any plan. Thus, running out of options, it makes the task of central banks to steer the economy – let alone bringing inflation back to around 2% - more and more difficult.

Also drawing more and more attention are the longer-term negative effects on the social fabric. In countries with the strictest social distancing measures, the economic effects are generally the highest. People with the most vulnerable labour market positions are ultimately hurt the most, mitigating measures by governments to help people financially bridge this containment period not taken into account. The longer the containment measures are kept in place and the lower the government support is, the stronger the negative effects on society will be, translating in growing inequality.

People with a weaker labour market position, such as self-employed or flex-workers, are hit hardest. ‘Flexible’ essentially means unprotected. Flex-workers usually do not have any social security benefits; no work means no income. In more egalitarian countries, like in Europe, this effect on inequality is less extreme. Existing social security arrangements such as unemployment benefits cushion the decline in income. In addition to that, several countries introduced extra income transfers to self-employed or others not entitled to unemployment benefits. In some countries this has taken the form of unconditional cash payments, comparable to a (temporary) basic income.

The differences in mitigating government measures against the economic fallout of the corona crisis can to a large extent be attributed to another aspect of inequality: those between rich and poorer countries. The economic effects of the pandemic will most likely be more severe in lower-income countries, leading to growing inequality. Labour in these countries is generally more informal and flexible than in richer countries. A lockdown here means that people cannot go to work and thus have no income. Government budgets generally do not allow for increased spending on social security. This situation is aggravated by an outflow of (foreign) capital and usually a strong devaluation of local currencies against the US dollar.

The current crisis accelerates social trends that already existed: the differences in opportunities between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ in both rich and poorer countries. The unprecedented policy measures, which even include elements of a basic income, will not be enough to turn that trend.

In addition to the above, ‘scarring’ to economic activity can be severe after such a sharp downturn, as previous recessions, especially the euro crisis, has shown. Scars left by reduced investment and bankruptcies may run more extensively through the economy. Confidence effects together with tighter financial conditions can also lead to less investments going forward. Scarring can also result from increased social inequality, debt overhangs and toothless fiscal policies because of debt overhangs and powerless monetary policies stuck at the lower bound.

This all means that we do not expect that the world economy will resume its course as it did before the corona-outbreak, nor do we think it should.

And then? Time for a resilient, sustainable recovery

The above analysis leads to the obvious question: should we restructure the economy to the pre-corona economy? With all the predictable longer-term problems as mentioned above? Our answer to that question is obvious: No!

The corona pandemic has finally brought us to the crossroads that we were heading to anyhow, where we have to make the choice between merely fixing our current economic system, or transforming it into a more resilient, sustainable and inclusive system. From the above analysis, our choice should be clear: transform it.

As also highlighted in our vision paper ‘A radical agenda for economic transformation’ it is time to change. Maybe now more than ever. This pandemic has shown once again that our economy is not resilient against large exogeneous shocks. In our vision paper we present our views on the kind of society we want to live in, first and foremost from a sustainability point of view. Now is the moment to talk very practically about a transition from a sustainability and resilience point of view: a glimpse of a more sustainable society that could emerge from this crisis. If governments are spending a lot of money to help their societies through these difficult times, why not do so in such a way that the economy will be reconstructed in a more sustainable way. Three issues ask for immediate attention with regard to the macro economy: What to save from our current system, how to do that and how to build a more resilient, inclusive economy on that foundation.

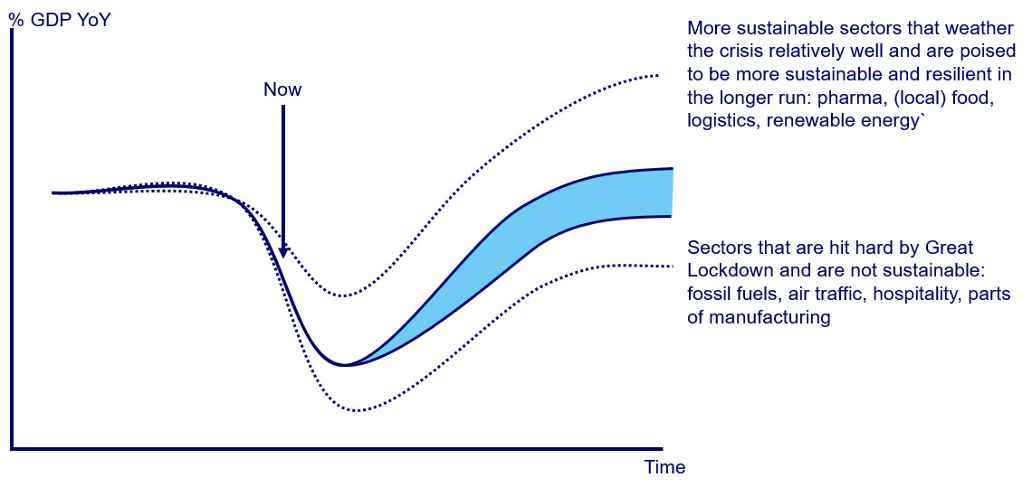

Save your money: don’t save everything

This economic crisis costs a lot of money. Estimates of the IMF show that about 10% of GDP gets wiped out. Given the enormous price it is valid to ask whether everything should be saved. In our view, there are several industries that need not necessarily be rescued and some that should preferably not be rescued at all. A large part of the fossil fuel industry, currently suffering from the double blow of demand fallout and low oil prices, should not be incorporated in rescue plans. These are the ‘stranded assets’ already seen as risk by supervisory institutions. If they are close to the shore, let them strand. Other, clearly harmful activities that are currently in trouble, such as aviation, mining, (international) tourism and several manufacturing sectors should not necessarily be saved. It does not mean –not even in the case of the fossil fuel industry – that these sectors should disappear instantly. At this point we have the choice to either save them, or let creative destruction have its way and have those industries be replaced by more sustainable alternatives quicker than anticipated.

The money otherwise spent on airlines or aircraft manufacturers is probably more than enough to help workers that become unemployed to bridge the gap towards a new job.

In addition to that, there may appear substitution effects between sectors as a ‘normal’ consequence of this Great Lockdown: some sectors will probably structurally benefit from changing consumer behaviour. Think about home delivery services, IT companies big in teleconferencing and online services, ranging from education to health.

For every economy, such choices have different consequences. It is estimated that for the 20 largest economies the effects on the ‘old’ economy differ from -2 to -7%. Countries that are hit more severely are those with more fossil fuel exports and tourism, such as Indonesia, Spain, Russia and Mexico. These effects can be mitigated by using fiscal policies to bolster more sustainable economic activities.

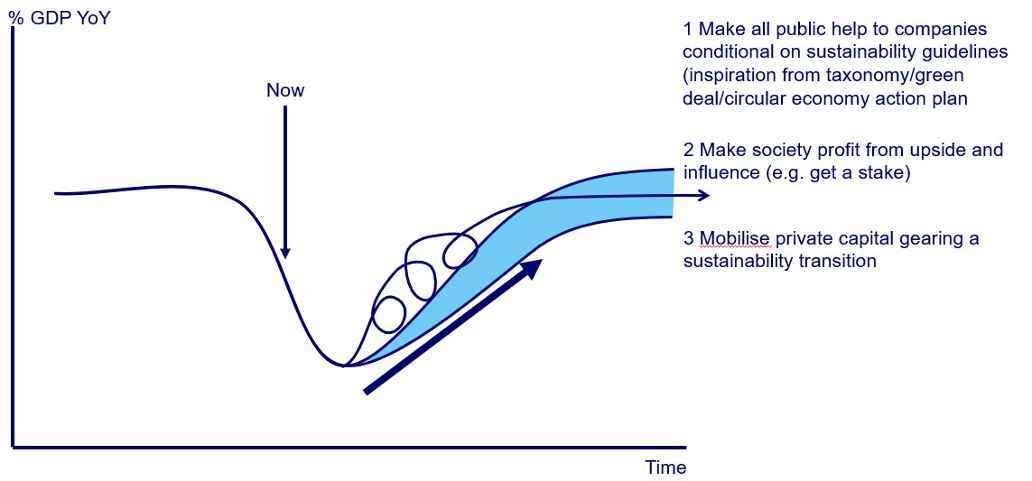

How to save: gearing a sustainability transition

In general, the policy agenda for most countries is quite clear. If a government has sufficient fiscal room, equity injections and grants will be the right instrument to help companies if their solvency is the problem. Is liquidity the challenge, temporary measures like a tax waiver, wage subsidies and direct loans (to e.g. SMEs) can be used. If governments have only limited fiscal space, solvency issues are difficult to overcome. Liquidity problems can more easily be overcome, for instance by umbrella guarantees with public banks.

To help households, a similar agenda can be drafted, again if there is enough fiscal room. Otherwise, is the best options are to strengthen existing social safety nets, provide targeted sector- or locality-based transfers (in money or in kind) and/or direct provisions for basic needs. If the budget allows, one-off (unconditional) universal transfers and in-kind provision of public goods (especially health care) can help. If the social safety net is already rather elaborate, automatic stabilizers should do their job, combined with extended coverage and benefit levels to overcome the first phase of the crisis.

This general idea of government policies can be enhanced, especially on the business side by some transitional guidelines. Economic, social and environmental viability is important for companies’ survival in the long run. As the bank bailouts in 2008 made clear, the government as a stakeholder can change the culture of an organisation and change its business model. It will, in the end, also affect market outcomes. We do not have to invent new policies for that. The conditions for government support can be pegged to the already existing targets to reduce carbon emissions in for instance the European Green Deal, but also more globally, in line with the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015. In addition to that, new targets set for the design of sustainable products and circular production processes by the European Commission in the new Circular Economy Action Plan can also be used as a guidance for state aid and to gear a sustainability transition. Especially in sectors with higher ecological footprints, ranging from mining, transport and manufacturing, and food and agriculture, support can be made conditional by setting targets for a sustainability transition.

In addition to that, (substantial) support should only be given in exchange for an equity stake in the company. This should at least count for large, listed companies, the same way as for banks in the financial crisis more than ten years ago. An equity stake will ensure that (1) the transition agenda as one of the conditions on which the aid granted is closely monitored, and (2) that the state may also profit from the upside of its investment in the longer run.

Thirdly, private capital should, now more than ever, be mobilised to gear the transition. Since dedicated public funding will become scarcer, private funds should contribute more to financing the sustainability transition. Transparency, guidelines on sustainable investments (taxonomy) and impact reporting will help. But in the end, it will also be the asset owners – both retail and institutional – who really want to gear a sustainability transition. Ultimately, it is about making the right choice of who and what to save, and also helping to shift the sustainability transition into higher gear.

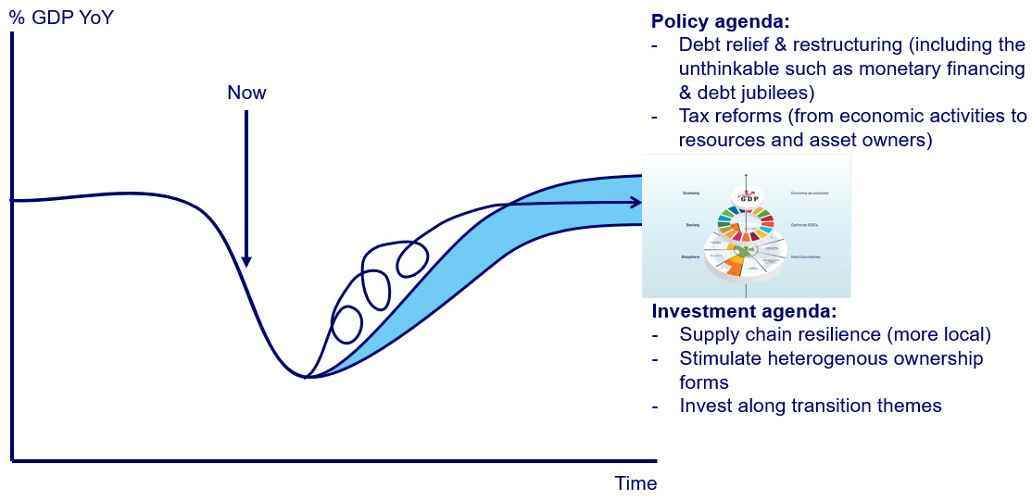

The goal - Building a resilient, inclusive economy

The exposure to health and financial risks is highly unequal, both within and between countries. More vulnerable households and workers will suffer more from the coronavirus and its economic effects. Policies can help mitigating these unequal impacts of the crisis. This would, however, imply international solidarity with countries impacted most by the crisis. This should start with an immediate debt relief and coordinated action by the IMF, helping to combat the first effects of the crisis. However, this will probably not be enough. It also requires further international cooperation and debt restructuring. We learned from the previous crisis that starting austerity measures too soon, hinders a more inclusive and stable economic recovery. So, everything should now remain on the table considering the restructuring public debts going forward: higher inflation, (targeted) monetary financing or debt jubilees. It is too early to judge, but it would be a mistake to conclude too early that it is over and still be stuck between rock and a hard place. In the end, a more resilient economy is an economy that is less debt ridden.

Furthermore, the policy agenda differs from country to country. But as part of the debt-reduction agenda, higher corporate tax rates and a wealth tax must be on the table. Experience from the past learns that one way to reduce public debt is to tax wealth. The other option, borrowing from the wealthy, has never been so successful. Taxing unproductive capital – such as wealth – harms economic activity less than taxing economic productive activities. As a by-product, it makes government budgets less dependent on the economic cycle.

What should also be part of this fiscal agenda is a shift from taxing economic activity towards taxing natural extraction and pollution: from labour to resources and from consumption towards carbon emissions. This helps companies with more sustainable business models to accelerate their business, while the polluters will be penalised.

Transitioning to a more resilient economy asks for more than ‘enough economic growth’ or ‘more jobs’. It requires changing the structure of the world economy. In this transition phase, we should especially favor local, more resilient sourcing in supply chains and diversity in production locations. In addition to that, more different forms of ownership – such as co-operatives, partnerships and commons – in addition to currently dominant forms of ownership.

This is a huge agenda. But the first decisions on that agenda have already been taken weeks ago: do we want to rescue our old, failing economy, or do we want to invest in a more sustainable resilient society? The choice is ours.

A radical agenda for economic transformation

Read our economic vision paper to learn how we propose to transform our economic system.