These developments have drastically altered the short-term outlook for the global economy. However, it confirms our analysis that the world economy has become ever more fragile over the past years. Any unexpected event, this time a new virus, shows that its fundamentals are very weak. The crisis has not yet reached its full depth and we foresee a global recession in case of an extended pandemic scenario. The pace at which events are currently unfolding, has severely increased the likelihood of this scenario in a matter of days.

Panic

The oil price crash and coronavirus sparked single-day movements on the equity markets not seen since the global financial crisis in 2008. Panic led to a repricing of risks and resulted in declining corporate debt markets and emerging market currencies, and a general spread widening. Just as we have gotten used to, the major central banks reacted promptly, attempting to ease investor sentiment. The easing measures, however, did not lead to market reaction that was hoped for. To us, this is a sign that financial markets have finally come to realise that central banks might be out of ammunition when the full impact of the coronavirus on the global economy materialises.

Governments are also trying to counter the immediate negative effects of the coronavirus and oil price war with fiscal stimulus. Fiscal policy responses are probably more needed and effective than monetary measures. Temporary targeted partial employment support and credit support for companies could be very useful measures in the short to intermediate term. Given the current record high global indebtedness, however, any positive effects of these measures could easily turn negative in the longer-term.

For the coming few weeks, we expect further poor economic news, volatile markets and negative investor sentiment. We therefore maintain our cautious stance and remain underweight in equities and neutral in bonds.

Coronavirus and oil price war disrupt status quo

Since mid-February, the quick spreading of the coronavirusis severely disrupting the unsustainable status quo in which the global economy had slowly manoeuvred itself since the global financial crisis in 2008. Economic activity is slowing down across the globe, and financial markets have fallen into a state of panic.

All major global equity markets fell more than 15% from their recent peaks. This marks the end of an era in which nothing could seem to hurt investor sentiment. Suddenly, the volatility index, a gauge for the level of stress in the market, spiked to near 50, its highest level since the global financial crisis in 2008. To calm down markets, the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) was the first major central bank to respond, on 3 March, lowering its policy interest rate by 50 basis points. Less than two weeks later, on 15 March, the Fed took even more drastic measures, making an additional full percentage point policy interest rate cut and announcing additional measures that it has not used since the global financial crisis. In the meantime, other major central banks have followed suit by also lowering their policy rates and/or introducing other easing measures. So far, however, these attempts failed to improve investor sentiment.

Shortly after the first market correction in February, on March 9, oil prices crashed by as much as 30 percent, causing a second shockwave of panic. Global equity markets tumbled even further, with single day movements not seen since the global financial crisis in 2008.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus spread further, leading to complete country lockdowns, as governments declared national emergencies. This resulted in new record one-day market declines. As it stands, the global peak of confirmed corona cases is yet to come.

A shock-cocktail of supply and demand

The impact of the coronavirus on the global economy will be felt through shocks to both supply and demand:

- Supply-side effects are quite straightforward. Economic activity will slow because factories and businesses are closing their doors, and supply chains – including labour – are disrupted because of quarantines and restrictions on mobility (social distancing). Supply chain disruptions can account for around 20% of the reduction of global growth in the period 2020-2021 (baseline scenario, excluding China). This implies a rather modest supply-side shock effect, which can be explained by the fact that once work is resumed, supply chains will recover quickly without experiencing severe longer-lasting effects. However, if disruptions are longer and heavier in more countries, the supply-side effects will have a much larger negative impact on global growth (excluding China) of between 35-40%. Companies can go bankrupt and investments can be postponed, which leads to more persistent economic effects.

- Demand-side effects are at least as important as their supply counterparts. First, the economy is hurt by lower demand in tourism, travel, hospitality and entertainment. If mobility is further restricted, demand will likely further decline and also affect other sectors. Increases in lay-offs and self-employed persons who don’t have any assignments lead to lower (aggregate) income and lower demand. Underlying deteriorating consumer confidence, partly driven by uncertainty, will add to this effect. Demand effects will account for around 80% of the drag in global growth over the period 2020-2021 (baseline scenario, excluding China). Half of this drag is attributed to tourism and the other half to consumption weakness. In case of an extended pandemic scenario, the increased importance of supply-side effects will mean demand effects will account for around 60-65% of the drag on global growth.

The importance of demand-side effects can for a large part be attributed to the extended aftermath of a demand shock. Demand doesn’t snap back like supply chain disruptions. Hysteresis due to confidence effects will slow down the recovery of demand. Ample supply of cheap oil might provide a partial relief on the demand-side, but this relief will likely be offset by the overall negative effects of the coronavirus containment measures and the oil price war on global macroeconomic and social stability. Moreover, longer lasting problems can lead to bankruptcies, and a general risk-off sentiment can put additional pressure on financial channels, amplifying underlying risks that were covered in the last years by very accommodative central banking policies and a general risk-on sentiment.

Severe recession risk for global economy

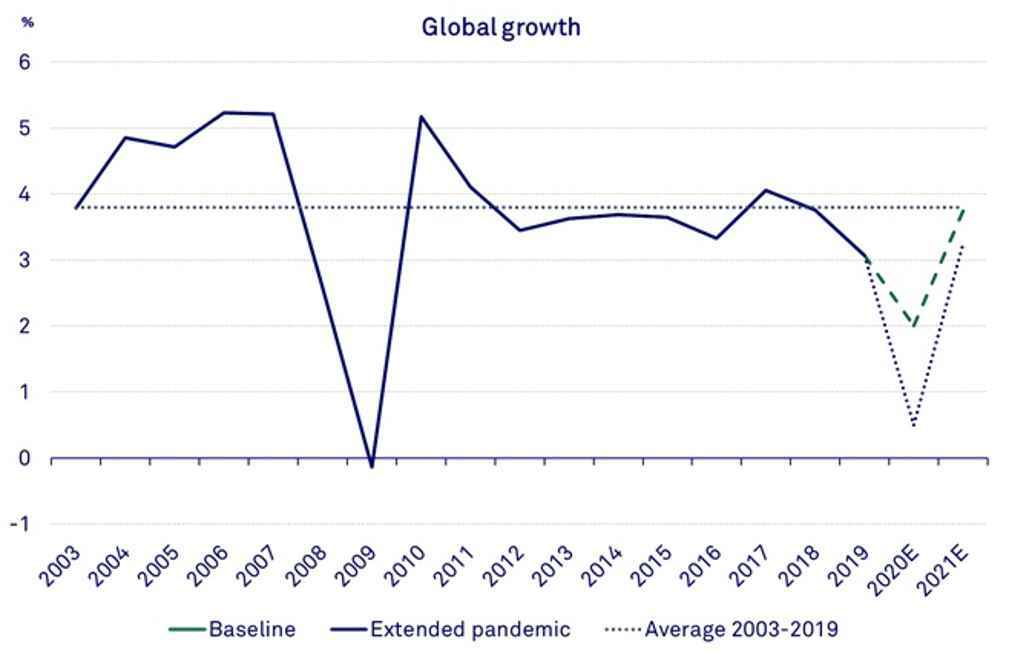

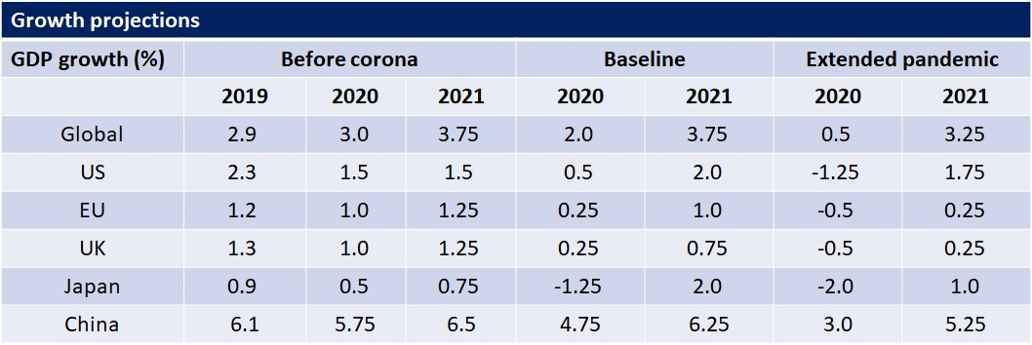

To assess the impact of supply and demand shocks resulting from the coronavirus and the oil price war, we have made economic growth projections for two main scenarios: a baseline scenario and an extended pandemic scenario.

In our baseline scenario, we assume that the coronavirus and the related oil price war will severely disrupt the global economy until the end of May. From then on, recovery will set in, leading to a slight pick-up in growth in the second half of the year, although not all growth that was lost will be recovered. In some regions, for example in China, the recovery may start earlier, while other regions, like the US, may lag. The biggest current uncertainty is how quickly the recovery will start, as we do not yet know the full size of the epidemic. In this scenario, most of the measures directly impacting growth, such as movement restrictions and shutdowns, will have been lifted by the third quarter.

In our extended pandemic scenario, we assume that around 15% of the global population will become infected. In such a scenario, the global health care sector will come under severe pressure due to a lack of capacity. Government measures causing social and economic disruptions will run into the third quarter. In this scenario, a global recession will be unavoidable. Below, we describe our economic growth projections for these two scenarios for the global economy and certain key regions/countries:

- Global economy: Overall, the eventual impact of the coronavirus outbreak and the oil price war on the global economy is still highly uncertain. The longer the virus roams around, the more clouded the economic outlook will be, and the longer it will take for the economy to recover. According to the interim economic outlook of the OECD, a “longer-lasting and more intensive” coronavirus outbreak could more than halve global growth in 2020. At the time of that publication, the oil price war and the complete lockdown of several countries had not yet materialised. Since then, the situation has deteriorated rapidly, and in our view the “longer-lasting and more intensive” scenario is likely to become true in a matter of days. Also, the impact might be even more severe than the OECD’s worst-case projection. In our new baseline scenario, we project annual economic growth to slow down from 3% to 2%, with developed countries slowing down to 0.50% and emerging countries to 3.75%. In our extended pandemic scenario, we project global growth to fall to 0.50%, with developed countries shrinking with 0.50% and emerging countries growing at 2%. This implies a recession in advanced economies and (substantially) less economic activity in developing economies. Differences in prospects can however be large, depending on the direct effects of corona (persons infected and national measures), trade openness and financial turbulence.

- China:The effects of the coronavirus will severely dampen China’s economic growth of the first quarter of 2020. It will take time before the economy is up and running again. Any potential pick-up growth will only materialise in the second half of the year.

- Japan: Economic data so far shows that other Asian countries were the first after China to be hit, as they are economically closely tied to China. Being in a weakened state already, Japan has likely been pushed into a recession by the coronavirus. The South Korean economy will also take a hit, as this country reported the second-most coronavirus cases in Asia (after China).

- Eurozone: Economic growth in the eurozone will also be severely impacted by the coronavirus, having the most confirmed cases outside of China. This had already led to substantial measures that will negatively affect growth. On top of that, the eurozone economy, more than the US economy, is also closely tied to China via supply chains and exports. Improvement of the global economy is vital for the eurozone economy.

- United Kingdom: The outlook for the UK was already weak before the outbreak of the coronavirus, as a result of Brexit. The virus has likely already impacted the UK economy. Tourism has taken a blow, and the slowdown in the eurozone affects UK manufacturing and services exports. A swift rebound in the second half of the year is not very likely, as the trade negotiations with the EU will probably still be going on.

- United States:Though less dependent on external partners than the eurozone, the US economy will also be impacted by the coronavirus. The oil price war will more severely impact the US economy, however, as the rapidly expanding shale gas industry has made the US a net exporter of oil. These shale gas companies will now come under severe pressure, as their breakeven price is much higher than that of conventional oil producers. This will likely hurt the US energy sector, with spill-over effects to other sectors.

- Emerging countries – ex China: Emerging market countries besides China are both directly and indirectly impacted by the coronavirus and the oil price war. The magnitude of confirmed cases in for instance Iran has led to a complete shutdown of the country, leading to an implosion of the economy. Oil-producing emerging countries are of course also directly affected by the oil price war, as they see their oil revenues dampen. This analysis can be extended to other net commodity exporting countries, as commodity prices in general are experiencing lower demand due to coronavirus disruptions. The global risk-off mode related to the outbreak can also have negative indirect effects, as it is already leading to reduced capital flows to emerging markets and depreciating local currencies. This will likely outweigh the potential benefits of reduced oil prices for non-producing emerging countries.

Targeted fiscal and monetary measures more vital than ever

The current situation asks for a decisive and forceful policy response: both monetary and fiscal measures are needed to contain this crisis as much as possible. The fragile state of our global economic system makes the choice for the right kind of policies even more vital. The highly accommodative monetary stance of the world’s main central banks, the inflated financial markets and the record-high level of global debt are weighing on the current crisis. A substantial part of the global population is more vulnerable than ever, as they have not benefited from the decade of elevated worldwide economic growth.

The growth projections presented above are estimates of the overall yearly impact on economic growth. The effects of the current crisis on the macroeconomy and financial markets, however, will unfold in different phases. There are four main phases (see also the figure at the beginning of this article). Each phase requires a different policy response.

The first two phases -China virtually coming to a standstill and the resulting global disruption in several economic sectors - require fiscal and monetary policies that address the short-term crash effects:

- Fiscal policies are needed to provide liquidity lifelines for companies experiencing difficulties due to supply chain disruptions or reduced demand. Delayed tax and social contribution schemes are the most straightforward means to provide this extra liquidity for businesses. Another way is temporary targeted partial employment schemes, making state support available when workers can’t work at full capacity. Additional support for health care is also needed in this stage. So far, it seems that these measures have been or are being implemented at the national level.

- Monetary policies are needed to complement fiscal policies, to ensure that there is indeed enough liquidity available to ease any stress in short-term funding. This can be done through for instance repurchase agreement transactions, like the Fed has done.

Phase three - the general global disruption - requires stepping up of fiscal and monetary policies:

- Fiscal policies must be used to provide all the necessary funding to facilitate the best possible healthcare. Additionally, certain sectors will now face severe and extended losses of revenues, causing a more structural problem than merely liquidity shortages. Small and medium-sized companies in particular will be hit. Forceful action to prevent bankruptcies is needed, in the form of tax reliefs and credit support. The temporary targeted partial employment schemes also need to be implemented more widely. Direct support to households might also be necessary. So far, these types of measures seem to gain traction at the national level, for instance in Germany with its Kurzarbeit scheme, in Italy with its tax holidays and relief from paying electricity bills and in Hong Kong and Singapore, where cash handouts are provided. Also at the international level, such measures are being considered, for example by Eurogroup president Mário Centeno, who recently advocated additional fiscal support measures at the eurozone level. At this stage, it is vital that governments take comprehensive measures, even if these test their fiscal capacity.

- Monetary policies must be implemented to address disruptions in financial markets, to ensure that the financial system remains stable and continues to function. Substantial liquidity must be provided, for instance through interest rate cuts, quantitative easing, the provision of cheap loans to banks and the favourable adjustment of rates on existing bank lending schemes. Additionally, capital requirements could temporarily be eased, to counter the impact of non-performing loans. All major central banks have implemented several of these measures. So far, however, the effects of most of these measures have been limited, given that monetary policies were already ultraloose. Policy interest rates are at historic lows and financial markets have already become addicted to never-ending quantitative easing measures. Taking additional measures is probably necessary considering the situation, but is also a dangerous move as we, once again, enter unknown territory.

During the final phase of recovery, fiscal and monetary policies need to focus on increasing consumer confidence and building up an economy that facilitates a sustainable transition that aligns with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Restauration of the unsustainable status quo of low global growth, low interest rates and low inflation that was build up in the period after the global financial crisis in 2008 is senseless. To this end, we need:

- Fiscal policies that help to avoid the likely hysteresis effects (for instance bankruptcies, lack of investments, long term unemployment) that could dampen demand. The most appropriate way to achieve this is via direct transfers to households. In addition, we need to focus on investments in climate mitigation and adaption and fulfilling the SDGs. Public policy agendas such as the European Green Deal help to steer public money to a more productive direction.

- Monetary policies need to be redesigned. The ultra-loose monetary stance eventually needs to be abandoned, and monetary policies need to be ‘greened’, i.e. changed into policies that facilitate sustainable economic growth by addressing the most pressing issues for future generations. This can for instance be done through targeted purchasing of corporate bonds, with the intention to foster low-carbon production, thereby stimulating and accelerating the transition to a low-carbon economy. This way, central banks can continue to play a vital role in our economy.

We haven’t hit the bottom yet

In our recent economic outlooks, we have consistently warned for market complacency. And in our vision paper A radical agenda for economic transformation we have explained that the current situation in most developed markets is unsustainable. In combination with ultra-loose monetary policies, this has led to inflated financial markets that do not reflect underlying fundamentals. We therefore took a cautious stance in our asset allocation. Of course, we could never have guessed that a global virus outbreak would be the cause of a change in sentiment and corresponding market sell-off, but our reasons for caution currently seem justified.

The coronavirus might be the black swan that many analysts were looking for. Although the overall outcome is still uncertain, our scenario-analysis above shows that a global recession is looming. We feel that some of the upcoming negative effects have not yet been fully priced in by financial markets. Moreover, there is a possibility that the feedback loops in the system result in problems in the financial sector (e.g. bankruptcies, asset price declines) feeding back to problems in the real economy. Therefore, we see no reason to change our current cautious asset allocation.

Uncertainty will prevail on the financial markets in the coming weeks. Needless to say that we will closely monitor all developments. If market corrections present opportunities, we will act accordingly. Relative to history, equity valuations still aren’t cheap , however, so for now we maintain our defensive equity allocation, as it is the best way to guard against further market corrections. Incoming economic data over the next few weeks will probably paint a very poor picture. Moreover, a lot of monetary easing has recently been priced in, and the question is whether central banks can (and should) deliver more. For our fixed income allocation, we remain broadly neutral, with a preference for credits with high-quality names. Overall, we keep investing in companies with solid impact and sustainability fundamentals, sound balance sheets, strong management teams and decent cash flow visibility.

The return of transitions

Also read our long-term economic outlook The return of transitions. This outlook reflects our investment philosophy. It is the basis of the strategic asset allocation for our impact equity and bond funds.